Sergey Gandlevsky composed this essay 20 years ago. He had reached a moment where, having summited a certain peak in contemporary Russian poetry, he had begun to be asked to teach master classes. In the essay, he looks back and traces the journey that he and others have taken, hoping to create a map for others to follow. I’ve always been haunted by the fact that most of us contemporary poets will be no more than what Gandlevsky calls the humus, the protective layer from which the most original of authors will spring. But perhaps, whatever our poetic aspiration, this is also good. There is something consoling about the idea that, as poets, we’re functioning as precursors, as matrix, as earth. For something yet to be born. — Philip Metres

Sergey Gandlevsky composed this essay 20 years ago. He had reached a moment where, having summited a certain peak in contemporary Russian poetry, he had begun to be asked to teach master classes. In the essay, he looks back and traces the journey that he and others have taken, hoping to create a map for others to follow. I’ve always been haunted by the fact that most of us contemporary poets will be no more than what Gandlevsky calls the humus, the protective layer from which the most original of authors will spring. But perhaps, whatever our poetic aspiration, this is also good. There is something consoling about the idea that, as poets, we’re functioning as precursors, as matrix, as earth. For something yet to be born. — Philip Metres

To Whom It May Concern

A poet doesn’t develop in a straightforward way — from Point A to Point B. Creative activity is like walking in place, circling back, and turning around. But, in the end, the attentive observer can distinguish in this muddle some stages of forward movement.

Let’s begin from ground zero. An adolescent of a certain type feels strong lyric urges and uses the first words that fall into his hand to relieve his soul. Out of goodwill, it is customary to talk about the spontaneity of childish opuses — but more out of goodwill. There is nothing spontaneous in the first samples of the pen. As a rule, there’s no intonation (no sense of voice), no revolution — nothing is yours. For the overwhelming majority of young poetry writers, the bout of adult graphomania passes as one grows up. The number of pretenders to the name “poet” grows smaller; you could even say that those who remain have a kind of distinctive immunodeficiency — they take verbalization too close to the heart.

That’s right. These writers cross over to the next stage and, sooner or later, find like-minded people, and poetic associations crop up. This is a time of chronic hanging-out, long conversations over long walks, demanding reading. Having befriended the living, a poet also chooses for oneself a long-dead company, according to one’s tastes, models for imitation, and strongly attaches oneself to some glorious literary trend of the past, not knowing for oneself if one will become a writer. It would seem that it’s a done deal. Not so. That’s not even the beginning.

Literature is a wide open space and in it one can learn how to exist — both in the professional and in the mundane sense. To receive pleasure from one’s own work and brighten your reader’s leisure, and if you’re lucky, to earn prizes and recognition. And in so doing, despite all of that, it’s possible not to write a single living word, nothing cutting to the quick; when that happens for the poet, and for the reader, a chill penetrates to the bone.

For the mass of writers, nothing in essence changes from the time of adolescent beginnings. Then, an inexperienced author composed awkward lines, seizing words from one’s inner reserve at random; the mature poet-professional has become experienced and writes strong poems, warily choosing a lexicon, intonations, and techniques from the general literary belongings of culture, as if on loan.

But one’s artistic means are nevertheless common, and in other words, still foreign, still not yet one’s own. Here’s the bad luck: it’s your life, but not your words! For a real poet, such a state of things is unbearable.

Therefore, a routine but nonetheless rigorous selection process lies ahead. The majority of writers will race casually here and there — to one aesthetic, then another, sometimes exclusively made for one poet’s needs, but already long ago having lost meaning and breed. Dozens of poetry books could be published without the authors’ names on the cover, because the composers of these books, in essence, are not really authors, but weak-willed mediums of a mode, school or tendency. The unsophisticated reader of this kind of writing has on one’s hands a problem not of particular personalities, but of the apostles of the literary commonplaces. The main character of Lev Tolstoy’s novella, The Death of Ivan Ilych, diligently furnished his apartment so that “it was charming … really, it was exactly the same as with all not entirely wealthy people who want to appear like the wealthy and therefore only end up resembling each other …” This is the middle class of writing — no more than a fertile layer, a humus, a protecting cultural ferment, a supporting means of dwelling that looks lived-in, ready for the arrival of a real author. This, perhaps, is essential and even healthy for the ecology of culture, as it guarantees the continuity of the process; but there’s quite an abyss between the level of literary pretensions of such nominal authorship and the real sense of its existence in literature.

A minority of writers, whose general state of being and self-consciousness (simply, who are talented!), doesn’t enable them to reconcile themselves to the fate of cultural plankton, will develop an allergy to “literature” in the routine sense of the word—what Verlaine had in mind when he said, “everything else is literature.” The exacting craftsman begins gradually to become burdened by art, which one has looked up at since youth, and which now demands from one and one’s colleagues-in-arms, in order to “end art,” so that, as Pasternak wrote, “soil and fate can breathe.”

This is what happens: deep within us, private impulses glimmer; let’s name them, for simplicity’s sake, our “spiritual life” — and these impulses want us to express them. We open our mouths and instead of us and for us, literature speaks.

To liberate our own language from literary bondage is a task that every worthwhile poet solves anew for oneself and in one’s own way. And the efforts to solve this very problem create genuine art. In the process of domesticating language, an author spends creative energy, which is preserved in culture for a very long time, if not forever. Everything loses its fragrance: the problematic of literary production goes out of date, original methods become antiquated in no time, artistic technique that was virtuoso for its own time becomes the property of the beginner, the meanings of words are forgotten or change so as to become unrecognizable. But the author who converts the language to their own faith will remain, and a good reader will sense as the presence of a style. When our general speech is transformed into what Nabokov calls an “individual vital dialect.” The doubtless and mysterious simplicity of a similar metamorphosis provokes our delight. I’m amazed when reading, that books by talented writers are typeset with some regular font.

Finding one’s own voice is a great and rare achievement, in which one can stop and dwell. And many do stop there. Just a handful of writers continue to develop past this point. Until this point, this stage, I’ve been talking about natural selection in the Darwinian sense — the biological competition of innate properties. Henceforth, not only talent is necessary — one needs to have something to say and to believe in the vitality of your expression, that is to possess those rare human qualities: a wide spiritual horizon, a restless mind, receptivity to experience, and ambition of a high standard. Now it’s not some concept of “literature” that becomes the bulls-eye point of vexation, but one’s own achievements. To duplicate them, meaning to multiply that “literature.” I think that this is far from some calm fate — it is a protracted battle with oneself. A personality of such a scale is doomed to aesthetic discoveries: an author’s style has to correspond to the rate of his human development. Sometimes it seems that in a given instance the creation of a masterpiece is not the end in itself of creative efforts, but a collateral result of a whole life activity. Of course, keep in mind this ideal figure is an absolute check, but without it we have a matter only of childlike vanity and work-therapy.

Please understand that I am not preaching, but simply talking about criteria and requirements which I’m showing to myself, and which I myself have not yet satisfied.

/ / / / /

Поэт не развивается прямолинейно — из пункта А в пункт Б. Творчество знает топтание на месте, возвращение, кружение, но, в конце концов, внимательный наблюдатель в этой путанице различит несколько стадий поступательного движения.

“Начнем ab ovo”. Подросток определенного склада испытывает сильные лирические позывы и пользуется для облегчения души первыми попавшимися под руку словами. Из доброжелательности принято говорить о непосредственности детских опусов, но больше из доброжелательности: ничего непосредственного в первых пробах пера, как правило, нет: интонации, обороты — все чужое. У подавляющей части молодых стихотворцев приступ возрастной графомании с молодостью же и проходит. Число претендентов на звание “поэта” заметно сокращается; можно даже сказать, что остаются люди со своеобразным иммунодефицитом: принимающие словесность слишком близко к сердцу.

Так вот, на следующий этап переваливают именно они и рано или поздно находят себе подобных, возникают поэтические содружества. Это пора хронического застолья, многословных прогулок, взыскательного чтения. Дружа с живыми, молодой поэт выбирает себе загробную компанию по вкусу, образцы для подражания, крепко привязывается к какому-либо славному литературному течению прошлого, незаметно для себя самого становится литератором. Казалось бы, дело сделано. Не тут-то было; осталось, как говорится, начать и кончить.

Литература просторна, и в ней можно научиться существовать — и в профессиональном, и в житейском смыслах. Получать удовольствие от собственного труда и скрашивать досуг читателю, если повезет — заслужить премии и звания. И при всем при этом не сказать ни одного живого слова, никого не задеть за живое – когда у самого поэта, а потом и у читателя мороз проходит по коже.

Для массы литераторов ничего по сути дела не меняется со времени отроческих начинаний: только тогда неопытный автор слагал неуклюжие строки, выхватывая слова из словарного запаса наобум, а возмужавший поэт-профессионал набил руку и пишет крепкие стихи, осмотрительно выбирая лексику, интонации, приемы из общего литературного имущества культуры, вроде как берет на прокат. Но его художественные средства все равно общие, то есть чужие. Вот незадача: жизнь — своя, а слова — не свои! Настоящему поэту такое положение вещей невыносимо.

Поэтому предстоит очередной и не менее суровый, чем в отрочестве, отбор. Большинство пишущих так и будет беззаботно гонять туда-сюда то одну, то другую эстетику, когда-то кем-то созданную исключительно для своих нужд, но давным-давно растиражированную и потерявшую смысл и породу. Десятки поэтических книжек можно издавать, не указывая на обложке фамилий авторов, потому что сочинители книжек, по существу, и не авторы вовсе, а безвольные медиумы моды, школы, тенденции. Неискушенный читатель этих сочинений имеет дело не с определенными личностями, а с глашатаями общих мест литературы. Герой повести Льва Толстого «Смерть Ивана Ильича» прилежно обставлял квартиру: “… было прелестно <…> В сущности же, было то самое, что бывает у всех не совсем богатых людей, но таких, которые хотят быть похожими на богатых и потому только похожи друг на друга…” Вот и писательский средний класс — не более, чем плодородный слой, гумус, обеспечивающий культурное брожение, поддерживающий среду обитания в жилом виде к приходу настоящего автора. Это, может быть, необходимо и даже полезно в экологии культуры, ибо гарантирует непрерывность процесса и т. д., но какая пропасть между уровнем литературных притязаний такого номинального авторства и реальным смыслом его бытования в литературе!

У меньшинства пишущих, кому самочувствие и самомнение (проще говоря, талант) не позволяют смириться с участью культурного планктона, появляется аллергия на “литературу” в рутинном значении слова — его имел в виду Верлен: “Все прочее — литература”. Взыскательный мастер начинает исподволь тяготиться искусством, на которое он же смолоду смотрел снизу вверх, требует от себя и собратьев по цеху, как сказал Борис Пастернак, чтобы «искусство кончилось», чтобы «дышали почва и судьба».

Ведь что получается: в нас теплятся какие-то глубоко личные импульсы, — назовем их для простоты “духовной жизнью” — нам хочется высказаться, мы открываем рот — а вместо нас и за нас говорит литература.

Освободить собственную речь из литературной неволи — вот задача, которую для себя и по-своему решает заново каждый стоящий поэт. И усилия для решения именно этой задачи и создают подлинное искусство. В процессе приручения языка автор тратит творческую энергию, которая сохраняется в культуре очень надолго, если не навсегда. Выдыхается все: устаревает проблематика произведения, тиражируются некогда оригинальные приемы, достоянием начинающих становится виртуозная для своего времени художественная техника, позабываются или до неузнаваемости изменяются значения слов, а вот авторский трепет при обращении языка в свою веру остается и ощущается хорошим читателем как наличие стиля. Когда наша общая речь превращается в “индивидуальное кровное наречие” (В. Набоков). Безусловность и таинственная простота подобной метаморфозы вызывает восторг. Мне даже чудится при чтении, что книги талантливых писателей набраны каким-то особенным шрифтом.

Обретение собственного голоса — большое и редкое достижение, на котором можно и остановиться; многие и останавливаются. Считанные единицы продолжают развитие. До этого, последнего, этапа речь шла о естественном отборе в дарвиновском понимании — биологическом конкурсе врожденных способностей. Отныне необходим не только талант — нужно иметь что сказать и верить в насущность своего высказывания, то есть обладать недюжинными человеческими качествами: широким духовным кругозором, непраздным умом, восприимчивостью к опыту, честолюбием высокой пробы. Теперь мишенью досады становится не какая-то там “литература”, а собственные былые достижения. Дублировать их значит множить ту же “литературу”. Думаю, что это далеко не покойная участь — затяжная борьба с самим собой. Личность такого масштаба обречена на эстетические открытия: авторскому стилю придется соответствовать темпу собственно человеческого развития. Иногда кажется, что в данном случае создание шедевра не самоцель творческих усилий, а побочный результат всей жизнедеятельности. Конечно, принимать во внимание подобную идеальную фигуру — очень гамбургский счет, но без него мы имеем дело лишь с тщеславным ребячеством или трудотерапией.

Поймите меня правильно: я не проповедую, а просто рассказываю о критериях, которые предъявляю себе самому и которым к своим пятидесяти годам мне не удается соответствовать.

/ / /

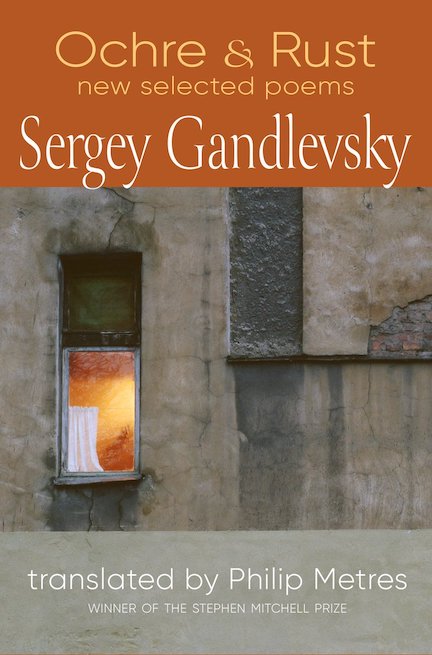

To to acquire a copy of Ochre and Rust: New Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky, translated by Philip Metres, published by Green Linden Press on October 10, 2023, 130 pages, $18.00, click here. Please note that the essay above is not included in this collection.

To to acquire a copy of Ochre and Rust: New Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky, translated by Philip Metres, published by Green Linden Press on October 10, 2023, 130 pages, $18.00, click here. Please note that the essay above is not included in this collection.