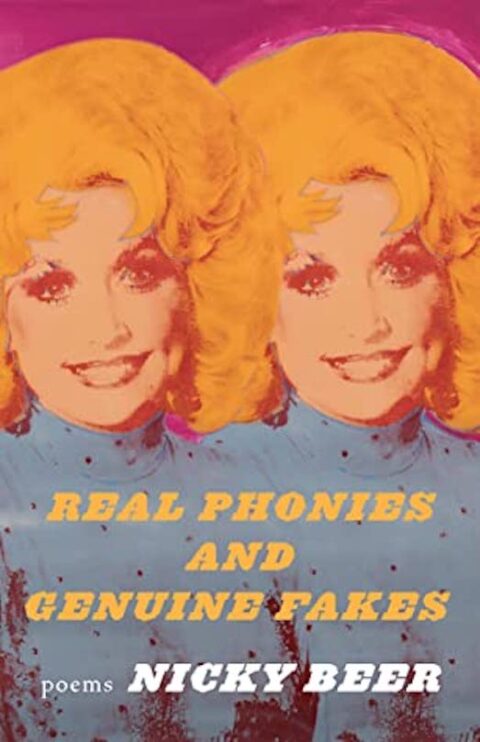

Nicky Beer’s Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes does what the title says it will do: it flips the script. There are two of everything in this book, male and female, vision and revision, Dolly Parton and drag Dolly Parton, lady sawed in half and lady behind the illusion. There is a real and a fake, and more often than not, the object upon which the poet casts her eye and devotion is the fake.

But perhaps not — the illusion is sometimes more real than the original, and this is half the point. Beer is clearly fascinated by the question of provenance and the genuine. What is an original, anyway? What makes it so, and why is that more real than the replica of itself? She quotes Dolly Parton, the book’s guiding spirit, as saying of the men in drag at Dollywood, “some of them look more like me than I do.”

But perhaps not — the illusion is sometimes more real than the original, and this is half the point. Beer is clearly fascinated by the question of provenance and the genuine. What is an original, anyway? What makes it so, and why is that more real than the replica of itself? She quotes Dolly Parton, the book’s guiding spirit, as saying of the men in drag at Dollywood, “some of them look more like me than I do.”

Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes is a book that revels in the play inherent in dress-up, finding its central subject in that creative act and what it says about our human desires both to get to the root of things in order to understand, and to subvert that objective with magic and obfuscation.

If it sounds like I am writing about poetry itself — the entangled twin desires for truth laid bare and lyrical sleight of hand — that’s because the book operates at one level like an ars poetica, a manifesto about the poet’s belief in the structures of our world and her duty as an artist to use them. The poems themselves are minimally adorned: with few stanza breaks or movements away from the left margin of the page, she draws us in by their seeming straightforwardness. There are no visual highwire acts here, but within the straight lines, images begin to contort. In the short poem, “Sawing a Lady in Half,” its full three lines read:

they want it to be true

and don’t want it to be true

that they want it to be true

Which is to say that our own minds contort as we try to make logic of what is impossible to believe — and as we try to tame our desires for magical (even violent) transformation into accepted limitations. The lady sawed in half may be the most real version of herself, so desired is her existence by the magician and viewer.

In subsequent poems, Beer ventriloquizes other speakers, like a plagiarist, the Stereoscopic Man, even a “re-creation panda.” What is a re-creation panda, you ask? Beer wants to tell you, and to share her delight in its weirdness. Here we’re in the world of professional taxidermy, where there is, she says, a particular category of work known as a “re-creation.” In this obscure art form, no part of the original animal is allowed to be used. So, in the poem, “Mating Call of the Re-Creation Panda,” the panda says, “I bear the bodies / of seventeen grizzlies on my back alone: / peeled, dried, Clairol-dyed and quilted / into a whole of me ,,, / Come closer. / Try to guess the provenance of my claws …”, and the effect is not morbid fascination but an affection toward the maker whose enormous effort, however oddly focused, so desired to make beauty from these materials and bring to life a creature from parts that did not belong to it.

Similarly, Beer tells the story of art forgers demanding to be revealed as those who perpetrated the fraud — they are irate to find that they are not believed. Lothar Malskat, a famous forger, is considered in the poem “Forged Medieval Church Fresco with Clandestine Marlene Dietrich.” The poem reads as an ode to his desire: “You can hardly blame Malskat for making her …” But by the end of the poem, Beer’s focus has moved to the painted movie star slipped into the fresco, and begins asking bigger questions: “Shouldn’t she pay / for making us want? … Tell me we don’t want all our goddesses flattened and pinned to a wall, wings spread and immobile.” A woman’s body is an object of desire, and a tool for transformation, which means it is inherently useful, and inherently at risk of violence in our use of it.

That’s the undercurrent of many of these poems, below their gorgeous and grotesque cast of characters, their circus tricks and intricate descriptive latticework. In the few moments where the speaker steps from behind the curtain to show us her own life, we hear a story shaped by pain:

I thought of the days before the pills,

and the large stone my bad chemicals made

for me to carry, a secret

sideshow attraction

to myself: The Woman Who Smiles.

Step right up and observe her

perfect imitation of a person

who doesn’t want to die.

This poem, “Two-Headed Taxidermied Calf,” can serve as a metapoem for the book, offering a key for how to perceive every other attraction to come. The poem reveals the reason for the fascination with the fakers and magicians. It allows the voice observing it all to peer out and tell us how (and why) she’s drawn to magic. There is a deep need for a cover-up in order to survive. She says that, in lying (which is to say, in inventing stories), she just wants “to see if I could still smooth a little poison / over glass and polish it / to a diverting flash, / a mirror showing everything / but itself.” So creating things — poems, pandas, lies — is a way of controlling the story, and shifting the focus away from one’s more painful experience.

My critique of the book is only that I want to know the speaker more from that interior space — to hear her speak a little longer, a little more often, having stepped out from behind the curtain of her show. I am always looking for her as I read. But if we think of this book as an exploration of human instinct, it is making the argument that hiding and performance are central to our nature, even necessary to our survival, and they equally serve the artist and the enraptured audience.

My critique of the book is only that I want to know the speaker more from that interior space — to hear her speak a little longer, a little more often, having stepped out from behind the curtain of her show. I am always looking for her as I read. But if we think of this book as an exploration of human instinct, it is making the argument that hiding and performance are central to our nature, even necessary to our survival, and they equally serve the artist and the enraptured audience.

We need to create, to reinvent ourselves into something better or more artful. Where the forger paints and the magician captivates with scarves and shimmer, the poet uses image and rich description both to deceive and to transform. The poet revises the poem again and again to better get at her meaning.

By the end, I had to wonder if there was such a thing as a fake at all. The panda instructs us to “imagine from what, or whom, / your own body could be collaged.” And it’s true, even biologically: the body exists in the process of re-creation, a constant sloughing and remaking of skin and hair and fluids. Who’s to say which version is the most imbued with our essential selfhood? The most graceful and capacious among us — Dolly Parton certainly being the model again — can allow for all of it to be real.

[Published by Milkweed Editions on March 8, 2022, 104 pages, $16.00 paperback]