TO GERMAN SPEECH

“Friend! Do not miss out on life./For the years are a-fleeing/

And the fruit of the vine/Will not intoxicate us much longer!”

(E. C. Kleist) (Ger.)

Killing myself, in constant contradiction,

As a moth that flies into the midnight flame,

I yearn to be delivered from our speech,

For all I am eternally indebted to it.

Between us there is praise without flattery,

And tight-knit friendship without hypocrisy –

Let us then study seriousness and honor

From the West, from an alien family.

Poetry, beneficial to you are thunderstorms!

And I recall a certain German officer,

The hilt of his sword encrusted with roses,

Stuck on his lips, the name of Ceres …

In Frankfurt, the fathers were still yawning,

None had heard neither hide nor hair of Goethe,

Hymns were composed, horses pranced about,

And, just like letters, in one place gamboled.

Tell me, my friends, in what corner of Valhalla

Were we so honored to crack nuts together,

What splendid liberty we had at our disposal,

What magnificent milestones you for me erected.

As though directly out of the almanac’s pages,

Out of its Article-One criminal code innovation, [2]

Descending undaunted into the crypt down steps

As into a cellar after a mug of Moselle wine.

An alien speech will be my warming ear husk,

And much had happened before I dared be born:

I’d been a letter, and I had been a verse of grape,

I’d been the book that you are dreaming about.

When I did sleep without complexion or storehouse,

As by a shot’s explosion, I was awakened by friendship.

Lord Nachtigal [3], grant me the cursed fate of Pylades

Or tear my tongue out – I have no need of it longer.

Lord Nachtigal, I’m still being trained, recruited,

For novel plagues, for the seven-year abattoirs.

Sound has constricted, all my words hiss, rebel,

But you live on, and I’m at peace in your company.

(August 8 — 12, 1932)

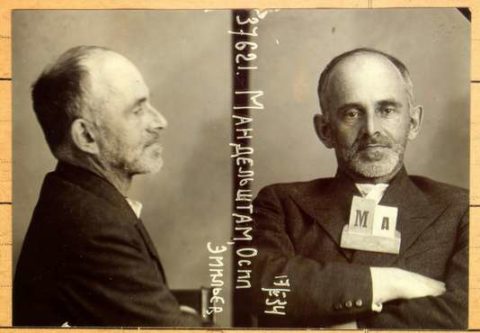

[1] Boris Sergeevich Kuzin (1903-1973): Mandelstam’s close friend, Soviet theoretical biologist (a Lamarckian), and German translator.

[2] Article 1. The task of the criminal code of the RSFSR is the protection of the social order of the USSR, its political and economic system, of the dignity, rights, and freedoms of its citizens, of all its forms of property, and of the entire socialist legal order, from criminal assaults (1926).

[3] Gustav Nachtigal (1834-1885): German explorer and commissioner of Central and West Africa responsible for the establishment of the German colonial empire. A serious ethnographer, he rejected the notion of African inferiority and believed that colonies would help end the slave trade.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

ARIOSTO (2)

Europe lies cold. Night has descended upon Italy.

Power is repulsive like a barber-surgeon’s hands.

Were one could but fling the broad window open,

Sooner than soonest, upon the salty Adriatic.

Above the musky rose the buzzing of a bee,

In the midday steppe – the muscular grasshopper.

The heavy horseshoes of a winged stallion,

The sand hourglass is a yellow tinged with gold.

The viscous resin of the cicadas’ tongues made

Of Pushkin’s melancholy and Mediterranean hubris,

Like an invasive ivy clinging onto all, bravely

He lies, and chivalrously hams it up with Orlando.

The sand hourglass is a yellow tinged with gold.

The muscular grasshopper in the midday steppe –

Our broad-shouldered liar soars straight to the moon…

Courteous Ariosto, cunning ambassadorial fox,

Eternal succulent, flourishing fern, sailing vessel,

On the moon you heard the oatmeal porridge voice,

And at court, among the fish, scientist was councilor.

Oh, city of lizards, in which lives not a soul –

Heartless Ferrara had borne such sons by witches,

And judges, and kept them on a stake and chain,

And the sun disc of orange mind rose in the wildness.

We are amazed to see the butcher’s open-air shop,

A babe fallen asleep beneath a netting of fat blue flies,

Yearling lamb in the yard, a monk riding a donkey,

The Duke’s soldiers, slightly inebriated and daft

From drinking too much wine, the plague, and garlic –

And by an impending sense, like sunrise, of absence….

(May 1933 / July 1935)

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

ROME

Where those loud, croaking frog fountains,

Splashing brashly, coming to life, sleep not,

And, once awakened, intensify their cries

With all the might of their throats and conchs,

The city that nods its agreement to those in power

Gushes with waters flowing from underground –

Lighthearted antiquity, summery, brazen,

With greedy gaze and flat-footed of heel,

Like unto an Angel’s undisrupted bridge

In the placidity above the yellow waters –

The city sculpted by the swift of the cupola

Out of the alleyways and passage lane drafts,

Deep blue, ashen, reduced to absurdity,

In the drumming agglomeration of homes –

You, mercenaries of coagulated blood,

Italic militia’s black-shirted centurions,

The long deceased Caesars’ riled up pups,

Transformed into a nursery for murder …

All of your orphans, Michelangelo,

Now embodied in shame and in stone –

The night, damp from tears, and innocent,

Youthful, fleet-footed King David,

And the bed sheets upon which immobile

Moses reposes in the form of a waterfall –

Might emancipated and leonine austerity –

Are silent in quiescence and in thralldom.

And the deliberately moving Roman man

Has raised the furrowed flights of stairs

Into the plaza of rivers flowing down the steps,

So that his steps resound, like honorable deeds,

And not for those maimed and disfigured,

Like the sluggish and languorous sponges.

The pits of the Forum are freshly re-dug,

And the gates flung open again before Herod.

And above Rome, the ponderous chin

Dangles of that degenerate tyrant.

(March 16, 1937)

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦