The First Step

The poet Eumenis, a young beginner,

complained one day to Theocritus:

‘For two years I’ve been writing and rewriting

and a single eclogue’s all I have to show,

my one finished work. I’m at my wit’s end.

I see how steep the stair of poetry is,

how high it reaches, yet here I am, no farther

than the first step. From where I stand

I know the climb will be too much for me.’

Theocritus answered him: ‘That kind of talk

is disallowed, an affront to poetry:

to stand on the first step should make you proud.

You should be happy with the work you’ve done.

It is no small thing to have come this far.

Achieving this much is already glory,

for negligible as this first step seems

it elevates you to a different plane.

If you’ve come this far, it means you must belong

by natural right in the city of ideas.

And to be admitted there as a citizen

is no easy or no ordinary thing.

No dubious character has ever fooled

the legislators in that agora.

It is no small thing to have come this far.

Achieving this much is already glory.’

* * * * *

Dionysos in Procession

The artist Damon (who’s to equal him

in the Peloponnese?) completes his Parian

marble ‘Dionysos in Procession’.

First comes the god, all power and glory, striding:

Intemperance next, and staggering by his side

Intoxication, pouring out the red

for satyrs, from an amphora twined with ivy.

Then Sweetwine, lazy-eyed, a little wobbly

but dainty on his pins, and then the trio,

Carouser and Musician and High Doh,

who bear the sacred torch and guard the flame.

Then Ritual, last, the most demure among them.

Damon adds a finishing touch. But as he works

his fee comes more and more into his thoughts:

three talents, no small sum, his proper due

to be paid out by the King of Syracusae.

Add that to his savings, and he stands

in the front rank, well got, a man of substance.

He can even run for office — Damon! Hurrah! —

He too on the Council! He too in the Agora!

* * * * *

The Satrapy

It’s hard on you, born and raised as you were

for the noblest, most magnificent challenges,

that this frustrating destiny of yours

keeps blocking recognition and success.

Trivial things are forever in your way,

pointless small concerns, despondency.

And then the tragic day when you acquiesce

(the day you allow yourself to acquiesce)

and take the road, a client bound for Sousa,

to present yourself to King Artaxerxes —

who favours you with a place at court

and grants you satrapies and all the rest,

positions you don’t want, but all the same

positions you accept in sheer despair.

Your soul seeks other things, repines for them:

the people’s praise, and the Sophists’,

that hard-won and most precious acclaim.

The Agora, the Theatre, the Laurels.

How could Artaxerxes give you these?

Where in the satrapy will you ever find the like?

And without them, how will you live? What sort of life?

* * * * *

Sculptor of Tyana

As you’ll have no doubt gathered, I’m no beginner.

These hands have gone through a fair amount of stone.

In my homeland, in Tyana, I’m counted famous.

Here too commission after commission

comes my way from senators, for statues.

Let me show you

just a few. Take a close look at this Rhea,

primal, noble, the model of endurance.

And Pompey too, the work I’ve done on him. And Marius,

and the African Scipio. Then Aemilius Paulus.

Honest likenesses, truly my best efforts.

And here (unfinished, granted) is Patroklos.

And over there, beside those blocks and drums

of yellowish marble, that’s Caesarion.

What preoccupies me just now is Poseidon.

For a good while I’ve been figuring how to shape

and fit the horses in. The entire group

has to surge above the waves, be so borne up

their hooves appear to skim each crest and whitecap.

Here, though, is my favourite in the workshop.

All of my tender care went into this.

On a warm summer day, when my reveries

were chasing the ideal, his form arose —

a dream I turned to stone in this young Hermes.

* * * * *

The Displeasure of Selefkides

Demetrios Selefkides was displeased

to be informed a Ptolemy had arrived

in Italy in a lamentable state,

in rags, on foot, with just a handful of slaves.

Henceforth their dynasty would be the butt

of Rome’s behind-backs laughter and snide jokes.

This Selefkides knows; knows they are little more

than houseboys in Rome now, now Rome decides

who keeps his throne, who loses, who succeeds.

Selefkides, yes, is aware of this,

but appearances, even so, should be kept up.

They should maintain a certain pomp and carriage,

not forget that they were, in spite of all, kings still;

and still did go (alas) by the name of kings.

That is why Selefkides was distressed

and offered Ptolemy sumptuous purple robes,

a glittering crown, diamond rings and gemstones,

a retinue of courtiers, liveried slaves

and a team of thoroughbreds, so he could appear

as any Ptolemy should appear in Rome:

an Alexandrian Greek monarch.

But Ptolemy, who had come to Rome to beg,

knew how it should be done and refused the offer.

There would be no flaunt or flourish. He approached

as if he were a nobody, in rags,

and boarded in the city with a tradesman.

Then came before the Senate, down on his luck,

a sad case and a beggarman in earnest.

/ / / / /

Constantine P. Cavafy (1863-1933) was a Greek poet, journalist and civil servant. His poetry was not published in book form during his lifetime. He was born in Alexandria, Egypt, where his Greek parents had settled in the mid-1850s. Cavafy lived in England for much of his adolescence, and developed both a command of the English language. After his father died in 1870, Cavafy’s mother returned to Constantinople with all of her children, then returned to Alexandria. But in 1882, the Cavafy apartment at Ramleh was destroyed when the British bombed the city in 1887. All of Cavafy’s books and papers were lost. He moved back to Constantinople with his mother until 1885, then rejoined his brothers in Alexandria and found work as a newspaper correspondent. In the late 1880s, he worked for a few years as his brother’s assistant at the Egyptian Stock Exchange, then became a clerk at the Ministry of Public Works. Cavafy stayed at the ministry for the next 30 years, eventually becoming its assistant director. In 1933, 11 years after leaving the ministry, he died of cancer on his 70th birthday. Cavafy wrote 155 poems, while dozens more remained incomplete or in sketch form. Some were published in magazines and newspapers. It has been suggested Cavafy, a gay man, was indifferent to or cautious about book publication due to the eroticism in some his work. The poems published here On The Seawall typify his poems of history in which he offered lively renditions of life during the Greek and Roman empires.

Constantine P. Cavafy (1863-1933) was a Greek poet, journalist and civil servant. His poetry was not published in book form during his lifetime. He was born in Alexandria, Egypt, where his Greek parents had settled in the mid-1850s. Cavafy lived in England for much of his adolescence, and developed both a command of the English language. After his father died in 1870, Cavafy’s mother returned to Constantinople with all of her children, then returned to Alexandria. But in 1882, the Cavafy apartment at Ramleh was destroyed when the British bombed the city in 1887. All of Cavafy’s books and papers were lost. He moved back to Constantinople with his mother until 1885, then rejoined his brothers in Alexandria and found work as a newspaper correspondent. In the late 1880s, he worked for a few years as his brother’s assistant at the Egyptian Stock Exchange, then became a clerk at the Ministry of Public Works. Cavafy stayed at the ministry for the next 30 years, eventually becoming its assistant director. In 1933, 11 years after leaving the ministry, he died of cancer on his 70th birthday. Cavafy wrote 155 poems, while dozens more remained incomplete or in sketch form. Some were published in magazines and newspapers. It has been suggested Cavafy, a gay man, was indifferent to or cautious about book publication due to the eroticism in some his work. The poems published here On The Seawall typify his poems of history in which he offered lively renditions of life during the Greek and Roman empires.

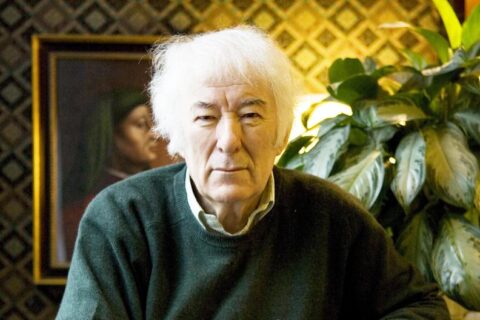

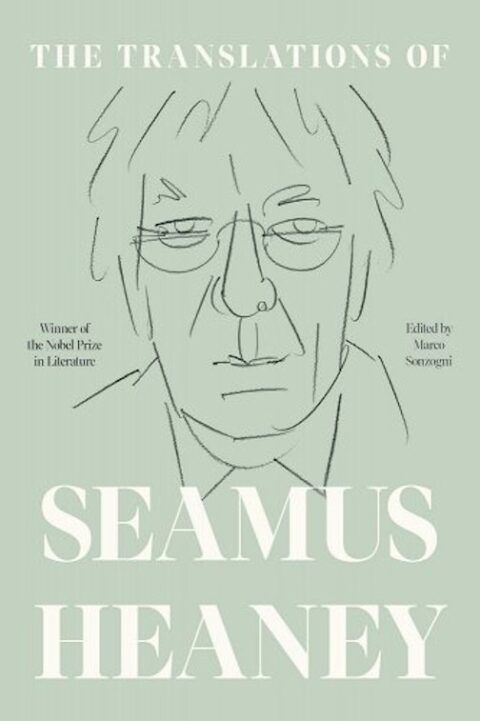

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) was born in Northern Ireland. Death of a Naturalist, his first collection ofd poems, appeared in 1966 and was followed by numerous volumes of poetry, plays, criticism, and translation. In 1995 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. His translation of Virgil’s Aeneid Book VI was published posthumously in 2016. According to his editor, Marco Sonzogni, Heaney produced 101 translated texts from 14 languages, most of which were published during his lifetime. He was working on the last of them in the months before his death in 2013.

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) was born in Northern Ireland. Death of a Naturalist, his first collection ofd poems, appeared in 1966 and was followed by numerous volumes of poetry, plays, criticism, and translation. In 1995 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. His translation of Virgil’s Aeneid Book VI was published posthumously in 2016. According to his editor, Marco Sonzogni, Heaney produced 101 translated texts from 14 languages, most of which were published during his lifetime. He was working on the last of them in the months before his death in 2013.

The Cavafy translations are excerpted from The Translations of Seamus Heaney. Edited by Marco Sonzogni. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by The Estate of Seamus Heaney. Introduction and editorial material copyright © 2022 by Marco Sonzogni. All rights reserved.

The Cavafy translations are excerpted from The Translations of Seamus Heaney. Edited by Marco Sonzogni. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by The Estate of Seamus Heaney. Introduction and editorial material copyright © 2022 by Marco Sonzogni. All rights reserved.

You can acquire a copy of the volume from Bookshop.org by clicking here.