Pol Pot’s Secret Prison

I remember sweating, shirt stuck to my skin, in a desolate jungle in Cambodia, while you sat at ease on the wooden platform, gnawing chicken dripping with grease, how you cracked the bones, sucked the marrow, told me about the prisoners you tortured during the genocide, when almost a quarter of the population perished in the late 1970s, as you worked as a Khmer Rouge interrogator at S-21, Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you said you had to.

Background

Born: 7 Jan 1951

Nationality: Khmer

Joined revolution: 1972

Became S-21 interrogator: 1976

Education: Literate, a bit of French

I remember your arrival, flip flops crunching gravel amid the rotten egg smell of diesel fumes, as you hopped off the back of a truck packed with passengers, wearing shorts and a striped white hat, not the monster I had been expecting as I waited at the entrance to a rural pagoda, which the Khmer Rouge had turned into a prison, filling the lake and nearby grounds with over 20,000 bodies, where a monk told me how the spirits of the dead haunt the grounds and possess people, where I expected to interview you near a small memorial piled with the bones of the dead and fronted by lotus-face incense urns, because I thought you’d be more likely to tell the truth, before you suggested we drive deep into the jungle, to a quiet place where we couldn’t be seen or heard, where I wondered if I was safe, as I sought clues about why you tortured over 50 people, sometimes for months at a time at S-21, Pol Pot’s secret prison, because, you insisted, you had to.

On April 17, 1975, after struggling determinedly for five years and making many sacrifices in the revolutionary war of national liberation against U.S. imperialism’s war of aggression, the people of Kampuchea and their Revolutionary Army have totally and definitively liberated themselves from exploitation and oppression by imperialism, neo-colonialism and all the exploiting classes. The whole nation has regained its soul.

– Pol Pot, Khmer Rouge leader, September 29, 1977

I remember staring at your back as you walked away, saying you had to urinate, though we had only just arrived, and half-hoped you’d disappear, but you returned, sat still as told you me how you farm rice and truck sandstone slabs on the side, to support your wife and five children who for years, like your friends and neighbors, knew nothing about how you worked in the S-21 “chewing group” that mixed “cold” and “hot” methods, verbal interrogation and threats then torture by fist, club, rod, electrical shocks, needles darted under nails, plastic bag suffocation, paying homage to the image of a dog, waterboarding, eating shit, drinking piss, said you didn’t like to use violence, even on the enemy, but still tortured them in Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

Objectives

- First, extract their information.

- Next, assemble many points for pressuring them so they cannot move.

- Propagandize and pressure them politically.

- Pressure and interrogate by cursing.

- Torture.

- Examine and analyze the responses to make the document.

- Guard them closely, prevent them from dying. Don’t let them hear one another.

- Maintain Secrecy.

— Notes from S-21 Political Study Session, 1976

I remember you staring down, unable to meet my gaze, as you told me how you interrogated morning, afternoon, and night, ate meals, attended meetings, and slept, but were isolated, forbidden from leaving the prison or visiting family, worried as interrogators and guards disappeared, but sometimes glimpsed things, like the time you time you saw prisoners, all skin and bone, blindfolded and shackled to beds at the S-21 clinic as the blood was siphoned from their bodies then sent to a military hospital, while you worked in Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

“Better to kill an innocent than risk letting an enemy remain alive.”

— Khmer Rouge slogan

I remember wondering if eyes can change color, as you told me how you got prisoners to confess by threatening to electrocute them, making their pupils bulge blue, because you had to.

Sometimes we have rage with [the enemy] that makes us lose our mastery, and for them sometimes it makes them incomplete ideologically and it makes them spin around in thoughts about life and death.

— S-21 torture manual

I remember the loud crack when, after you finished eating, after you tossed the remains of the chicken to a pair of ravenous strays who fought for your discards, after you fell silent, you struck the wooden platform so hard it shook, told me that’s how you pounded the table in front of the nineteen-year-old girl you were interrogating, terrifying her, making her urinate on herself as she sat shackled in Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

The purpose of torturing is to get their answers. It is not done for fun. We must make them feel pain so that they will respond quicker. . . Do not be too quick. That will make them die and we will lose their information.

— S-21 torture manual

I remember gazing at your misshapen ear, top half melted by shrapnel, when your tone suddenly softened, when you added that the girl was beautiful, that you pitied her, had secretly fallen in love with her, got furious because, barely literate and disoriented, she was unable to write a confession, so you did it for her, to end her interrogation, though it meant she would soon be killed, and how you lowered your voice, explained in almost a whisper, that you were a young man with urges, got frustrated and angry, because you wanted her, the two of you so close and alone in the isolated room, as you interrogated her in Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

You must be vigilant: First, rough work — careless work → conflict with the collective. Second, morality with females.

— S-21 Prison Interrogator’s Notebook

I remember you sticking a toothpick in your other ear, swiveling it between forefinger and thumb, probing oil and wax, as you told me how you were taught to torture, brief lessons, close observation, then trial through practice, the first time hard, then easier, so that, by the time the girl arrived, you were seasoned, knew just what to do, forcing her to reveal her supposed CIA network, name co-conspirators, and confess to treasonous crimes, including how, at the model hospital where she worked, her boss ordered her to shit everywhere, including the operating room, to ruin the hospital’s reputation, said you believed this, as you interrogated her for three months, writing and rewriting her confession in Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

Methods in making documents

We must organize them to write about their traitorous lives in a smooth and clean narrative that is practicably clear and has reasons, has a basis for espionage and infiltration inside us, in a step-by-step process according to their plans.

— S-21 torture manual

I remember thinking how, with your sunken eyes, widow’s peaked black hair, and matchstick mouth, you looked the part, then asking what you would say to the spirits of your victims, how you replied you’d bow down and apologize, how you now pray for them and make ritual offerings when you go to the pagoda, how you want to testify at the tribunal and tell the truth, and how you once apologized to the younger sister of the girl you tortured, who accepted your words as she sobbed it was important not to be knotted in anger and seek revenge, even as you told her you only did these horrible things in Pol Pot’s prison, because you had to.

Work schedule

5:30 Wake up and do labor

6:45 Bring the enemy to the interrogation site

1:45 “ “ “ “ “

5:30 Afternoon team meeting

6:55 Bring the enemy to the interrogation site

— S-21 Prison Interrogator’s Notebook

I remember the smell of decay as you told me this story, decomposition in the jungle heat, familiar from the rural Cambodian village where I did fieldwork in the 1990s, when survivors told me their Pol Pot stories, how their village was emptied so the Khmer Rouge could set up an extermination center, where more than ten thousand people were trucked and killed, and how, when they returned to their homes in early 1979, after the Khmer Rouge had been toppled, the villagers found their rice fields littered with mass graves and wells stuffed with corpses, and how, when the wind blew, it brought an unforgettable stench, which I later smelled at an exhumation site in Bosnia, of putrefied meat, fetid cheese, and fruit long gone bad, the same stench that wafted through S-21, as you interrogated her at Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

To keep you is no gain, to destroy you is no loss.

— Khmer Rouge saying

I remember you slowly rubbing menthol on your forearm, vapors cooling a mosquito bite you’d gotten as you spoke, and then, as we got ready to leave, how you went to urinate for a third time, how, as we drove out of the jungle, you pointed out a crater in the ground, made by a U.S. bomb during the civil war, from which a tangle of trees and brush sprouted from all sides, how we passed by a giant scarecrow sentry with a plastic bucket head, whisps of straw hair, and beaded eyes, armed with a stick to ward off disease and evil spirits, then reached the main road, where you asked to be let off so your son could get you, afraid you’d be seen with us by neighbors and shamed, then turning to look back at you as we drove away, as it started to rain, breaking the heat, droplets splattered on the back glass, making it hard to see you, as you faded from view, a man, stick figure, pebble, speck, then gone, feeling relief to no longer be deep in the jungle with you, as you gave excuses but no clear answers, but left clues to piece together from the horrible things you recounted, especially the story about the girl you tortured, how, despite your feelings for her, you terrorized her because you said you didn’t think deeply, believed in the Khmer Rouge cause, were indoctrinated and trained, became desensitized, regarded her as an enemy, stripped her of her individuality, turned her into a type, transformed her from a person who attracted you into an object of disgust, a defecating traitor, more of the counterrevolutionary scum you had to deal with while working in Pol Pot’s secret prison, because you had to.

Be determined not to hesitate in interrogating enemies.

Be determined to interrogate and get confessions for the Party.

Be determined to defend and build the country to be beautiful and bright.

— S-21 Torture Manual

I remember the grit in my mouth when, after traveling down a potholed one-lane road sided by a creek and rice paddies, wheels churning gravel, leaving dust in the air, after asking her sister what she thought about how you interrogated her sibling, banged the table, said it was out of love, and now asked for forgiveness, her sister clenched a framed copy of her sibling’s S-21 mugshot and sobbed, wondering how you could do such a thing to someone who was gentle, loved learning, was always happy to help at home before being forced to join the Khmer Rouge, and then, sitting in front of her thatch-roofed hut in a glade, surrounded by friends and neighbors, condemned and cursed you, remembered how irate she was when you two met, how she tried to hit you with a chair but was stopped, how she remains furious, fights her desire for revenge, wants you to stand trial, insists you didn’t have to.

Qualifications for joining the Party. 18 years or older. Already tested. Follows Party line, ideological and organizational stances of the Party. Good class pedigree. Clean morals and politics. Never involved with enemy. Clean personal history.

– Communist Party of Kampuchea Party Statutes

I remember, years later, observing an antique mural of the Buddha, saffron-robed and sitting lotus position under a Bodhi tree, a symbol of enlightenment, that hung on the wall behind the desk of a Cambodian civil society leader, a child survivor of the genocide, who remembers the revolution as a time when food was his god and each day a struggle for survival, when he lost dozens of family members, some killed by Khmer Rouge who are alive, who have sought forgiveness, which is extremely difficult to give, because an apology doesn’t take away the scars of genocide, a point he suddenly underscored by using you as an example, noting how much easier it is for a perpetrator like you to apologize and then move on from the moment, how the girl’s sister was left with two bad choices, reject or accept it, both paths unsatisfying, which creates an impossible choice for her, as a devout Buddhist who is supposed to let go of vindictiveness, but doesn’t want to insult the spirit of her dead sibling, creating a situation beyond Buddhism, beyond the ability of religion to heal, more so since you still excuse your interrogation of her sister, claiming you did it because, at Pol Pot’s prison, you had to.

“Don’t allow a worm to wriggle under your skin.”

— Khmer Rouge slogan

I remember wondering what the girl’s sister was thinking, when you testified at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in 2009, wearing an oversized grey jacket and staring down as you told the court in a monotone about Pol Pot’s torture chambers, when you were asked if you regarded the prisoners as animals, replied that you would prefer not to answer, which was an answer, confirming that you regarded the girl and the many other prisoners you tortured as subhuman, suggesting you were a true believer, willingly served the revolution, sought to destroy its enemies as you interrogated in Pol Pot’s secret prison not just because you had to, but because you wanted to.

/ / /

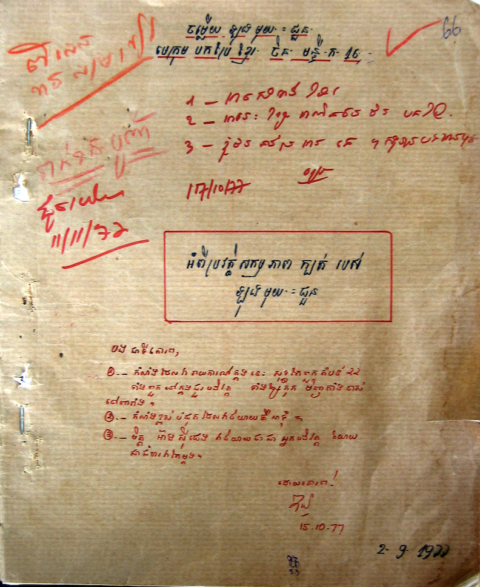

A prisoner’s “confession” …

Prison interrogators

The prison — now a genocide museum …

Sources: Author interviews, DK documents, Documentation Center of Cambodia archive, Khmer Rouge Tribunal proceedings and case file. Photos courtesy of DC-Cam/SRI.