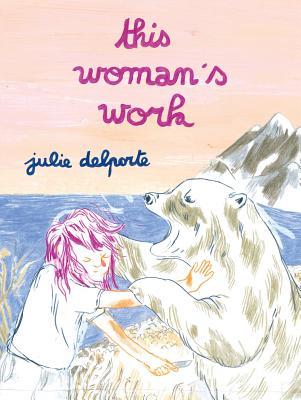

How do you draw the feeling of being unable to draw? Do you render it as blankness? Abstracted scrawls? Something that’s more precise, yet still evoking a sense of blockage? The question is a driving force behind two recent graphic memoirs, Julie Delporte’s This Woman’s Work and Ulli Lust’s How I Tried to Be a Good Person. Both reckon with relationships, which to some degree means reckoning with disruption — both books evoke how it feels just to want to be at the drawing table without disruptions that are both immediate (jobs, needy men) and more general (contemplating motherhood and success).

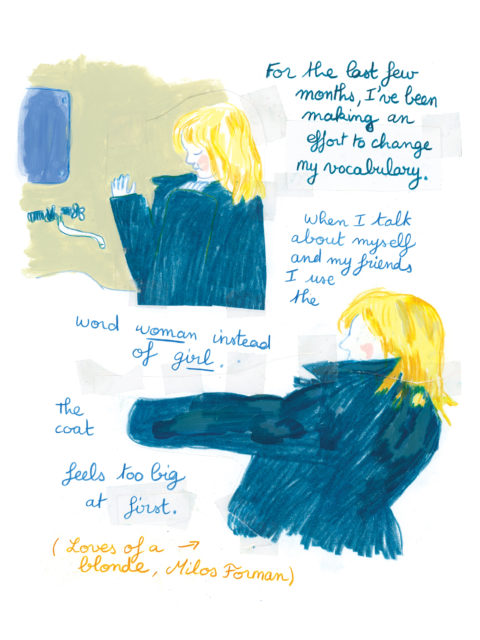

Delporte, a French-born artist now living in Montreal, frames This Woman’s Work around her possible pregnancy and fear of what it might mean for her. “I would have liked him to say I’ll take care of her / you’ll be able to draw / I’ll change the diapers / I’ll even nurse her,” she writes of her partner and imagined daughter. (Aleshia Jensen and Helge Dascher translated the book from the French.) The cursive, in colored pencil, is precise and school-primer perfect, but Delporte’s drawings are more deliberately uncertain and shadowy. Coupled with her partner in bed, she appears as if underwater. She struggles to draw her vagina, she writes, “having lived so long without an image of one.”

Delporte, a French-born artist now living in Montreal, frames This Woman’s Work around her possible pregnancy and fear of what it might mean for her. “I would have liked him to say I’ll take care of her / you’ll be able to draw / I’ll change the diapers / I’ll even nurse her,” she writes of her partner and imagined daughter. (Aleshia Jensen and Helge Dascher translated the book from the French.) The cursive, in colored pencil, is precise and school-primer perfect, but Delporte’s drawings are more deliberately uncertain and shadowy. Coupled with her partner in bed, she appears as if underwater. She struggles to draw her vagina, she writes, “having lived so long without an image of one.”

That anxiety sends her back to childhood, where she considers the constraints of girlhood, returning to memories of molestation by an older cousin. Delporte’s palette throughout the book comprises mostly primary colors, emphasizing washes of blue, and the rigid cursive is clear. Yet the images still convey a sense of uncertainty, incompleteness that sometimes shades into a quiet fury. A page of smears of paint is captioned “I feel like I’m carrying the weight of an old family story”; in a classroom, noting that in French grammar masculine take precedence, she draws a blue blackboard reading “The grammar I was taught still hurts.”

As the memoir shifts into her adulthood, Delporte’s line grows more precise while the imagery grows more fanciful and the questions more deeply philosophical. As a budding artist, she dreams of seclusion, and admires the Swedish troll-like figures, Moomins, created by the Finnish novelist Tove Jansson. Delporte’s fantasias of life on the sea, in the woods, run up against the blank drawing table and fear of failure. (“I google ‘imposter syndrome’ and start crying.”) The childhood assault, and her sense of other assaults beyond it, is inextricably connected to her need to create and her struggle to do so.

Delporte’s imagery represents the distance between what she wants to say and her frustration with finding a way to say it. Although she draws herself often, the book swims in metaphor — the Moomins, the landscapes, comets, birds. It’s also scaffolded with quotations from women artists — Jansson, filmmaker Barbara Loden, Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck, novelist Olivia Rosenthal, sculptor Louise Bourgeois –that underscore her place in a through-line of sidelined creativity. “It seems women will never have enough time to make art,” she writes, drawing herself on a beach, prone and faceless, on a cartoon seaside, the water a forbodingly deep navy blue.

Delporte’s imagery represents the distance between what she wants to say and her frustration with finding a way to say it. Although she draws herself often, the book swims in metaphor — the Moomins, the landscapes, comets, birds. It’s also scaffolded with quotations from women artists — Jansson, filmmaker Barbara Loden, Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck, novelist Olivia Rosenthal, sculptor Louise Bourgeois –that underscore her place in a through-line of sidelined creativity. “It seems women will never have enough time to make art,” she writes, drawing herself on a beach, prone and faceless, on a cartoon seaside, the water a forbodingly deep navy blue.

The most effective visual gambit — and Delporte’s ultimate pathway into productive creativity — is dreaming. Her dreams can be violent — she slays a polar bear with a knife, deep red on blue ice — but toward the end more hopeful. She dreams of creating a beguinage — a French community for lay women –populated by poets and artisans. “They write and read all day long,” she writes, under a wash of primary colors, suggesting a flag for her new community. The closing pages disrupt the fantasia and bring her back to Earth—she still has a real world, and real anxieties about motherhood to consider. But she’s found the form through which she can more fully evoke it.

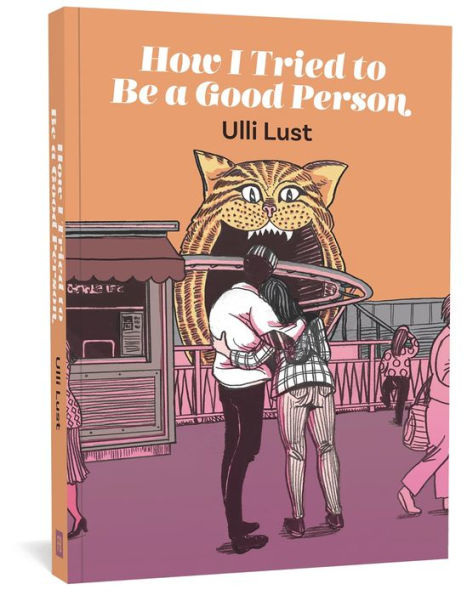

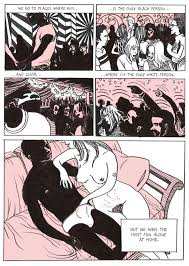

Ulli Lust, an Austrian-born graphic novelist, doesn’t share Delporte’s struggle with artistic syntax. How I Tried to Be a Good Person is a more direct and conventional graphic memoir about her days as a barely employed artist attempting to launch her career while navigating relationships with multiple men. Her romantic relationships are a function of an emotional free-spiritedness that’s somewhat subsidized — she has a son who lives with her parents in the countryside while she pursues her art in Vienna. But she’s also hemmed in: Her sense of altruism (the “good person” of the title) means she does a lot of self-sacrificing on men’s behalf. Chief among them is a young Nigerian immigrant, Kim, who’s supportive of her art but mostly sexually obsessed with her, and prone to manic and increasingly violent rages when he’s feeling denied.

Ulli Lust, an Austrian-born graphic novelist, doesn’t share Delporte’s struggle with artistic syntax. How I Tried to Be a Good Person is a more direct and conventional graphic memoir about her days as a barely employed artist attempting to launch her career while navigating relationships with multiple men. Her romantic relationships are a function of an emotional free-spiritedness that’s somewhat subsidized — she has a son who lives with her parents in the countryside while she pursues her art in Vienna. But she’s also hemmed in: Her sense of altruism (the “good person” of the title) means she does a lot of self-sacrificing on men’s behalf. Chief among them is a young Nigerian immigrant, Kim, who’s supportive of her art but mostly sexually obsessed with her, and prone to manic and increasingly violent rages when he’s feeling denied.

Lust captures her past in a way that conveys both her recklessness and sense of sheer pleasure in the world. She has no anxiety, as Delporte does, about drawing a vagina — full-page sex scenes are lavish fantasias. Other splash pages highlight moments of emotional intensity — dance clubs, landscapes, demolished buildings. But the counterweight to her free-spiritedness is her need to finish the children’s book commission she’s working on. Kim routinely interrupts her at the drawing table. (She lives on unemployment, trying to forestall the job-hunting the unemployment office keeps requiring.) Another on-again-off-again actor boyfriend presses her to go on a trip with him. “You can draw in Thailand, too!” he insists, unrealistically. Her moment of triumph — the finished book — is immediately undone by the full-page image of Kim all but smashing her door down to confront her over another imagined outrage.

The tension in Good Person derives partly from an artist being constantly denied that room of her own. But it derives also from her sense that the room itself won’t be enough — that being in the world is as critical to her identity as that drawing table. In the case of her choosing to stay with Kim, this seems agonizingly misguided. But with the distance of time, Lust is trying to accurately render her urge to be compassionate, even toward somebody who’s behaved monstrously toward her. Some of that springs from a simple sense of justice — she’s infuriated at how the Austrian bureaucracy treats immigrants. But she also concedes that sex played no small role either. The tension between empathy and passion feels irreconcilable to her for a long time, and it’s agonizing to witness; there has to be a better way to mature as an artist, you think. That she’s able to convey that tension so coolly and candidly, now, is a tribute to how much she learned from it.

The tension in Good Person derives partly from an artist being constantly denied that room of her own. But it derives also from her sense that the room itself won’t be enough — that being in the world is as critical to her identity as that drawing table. In the case of her choosing to stay with Kim, this seems agonizingly misguided. But with the distance of time, Lust is trying to accurately render her urge to be compassionate, even toward somebody who’s behaved monstrously toward her. Some of that springs from a simple sense of justice — she’s infuriated at how the Austrian bureaucracy treats immigrants. But she also concedes that sex played no small role either. The tension between empathy and passion feels irreconcilable to her for a long time, and it’s agonizing to witness; there has to be a better way to mature as an artist, you think. That she’s able to convey that tension so coolly and candidly, now, is a tribute to how much she learned from it.

[Delporte: Published by Drawn & Quarterly on March 5, 2019, 256 pages, $24.95 softcover

Lust: Published by Fantagraphics on July 16, 2019, 368 pages, $24.99]