What’s at the root of our current collective malaise, hard to define but surely there? Income inequality, maybe. Divisive politics, perhaps. Covid, overwork, underemployment, global conflicts. The supply chain about to deliver a shower curtaintwo days later than we’d like. That one person in the group chat. Something. Mark Edmundson has his own idea about this: We have become slaves to our super-ego, Sigmund Freud’s nattering, cynical killjoy that seems to revel in kneecapping our virtue and conscience. “A power that judges us, often irrationally, and demeans us, often without cause, does abide within us,” he writes early in The Age of Guilt, his slim jeremiad on the phenomenon.

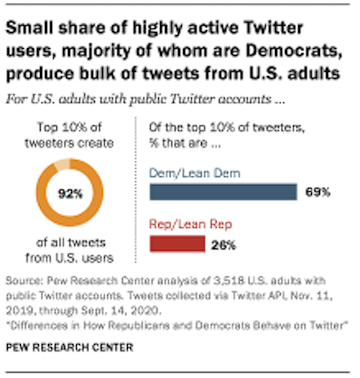

Did you bristle there, a little, at that mention of Freud? If so, by Edmundson’s reckoning, your reaction implicates you in the very problem that he means to address. We — and by “we,” he generally means well-educated Americans, and often college students, like those he teaches at the University of Virginia — have allowed our psyches to fall under the sway of a sort of cultural super-ego, which is determined to foreclose contemplation and replace it with snap judgments. Freud — outdated, patriarchal cokehead. Woody Allen —passe, smug, shallow abuser. Whomever Twitter is collectively angry at on the day you’re reading this — unkind, retrograde, uncivil. Twitter rage exemplifies Edmundson’s argument that the “online world” of the book’s subtitle has prompted our super-egos to take an outsize role in our discourse. This, he fears, has delivered all manner of negative social consequences: “As a literate and literary culture is displaced by a visual electronic one, we are in danger of losing contact with a consequential piece of wisdom about the human psyche.”

Did you bristle there, a little, at that mention of Freud? If so, by Edmundson’s reckoning, your reaction implicates you in the very problem that he means to address. We — and by “we,” he generally means well-educated Americans, and often college students, like those he teaches at the University of Virginia — have allowed our psyches to fall under the sway of a sort of cultural super-ego, which is determined to foreclose contemplation and replace it with snap judgments. Freud — outdated, patriarchal cokehead. Woody Allen —passe, smug, shallow abuser. Whomever Twitter is collectively angry at on the day you’re reading this — unkind, retrograde, uncivil. Twitter rage exemplifies Edmundson’s argument that the “online world” of the book’s subtitle has prompted our super-egos to take an outsize role in our discourse. This, he fears, has delivered all manner of negative social consequences: “As a literate and literary culture is displaced by a visual electronic one, we are in danger of losing contact with a consequential piece of wisdom about the human psyche.”

The Age of Guilt is constructed out of short, crisp chapters, and Edmundson writes thoughtful ones on the nature of the super-ego, how Freud developed it, and how its role as a social and individual psychic bully is distinct from matters of conscience, authority, and discipline. But Edmundson’s chief goal is to attach the super-ego and its turd-in-the-punchbowl qualities to the culture wars. The super-ego, he submits, is behind the worst of right and left politics. On the right it shores up the cult of Trump, “a surrogate super-ego, whose power is not only political but emotional.” On the left it gives us cancel culture, virtue signaling, woke posturing, and all the rest, making the world “a more shabbily puritanical place.”

Edmundson may make an effort to frame the super-ego as a bipartisan menace, but it’s clear that he sees more serious, thoroughgoing harm on the left side of the aisle. For all of his considerations of the super-ego and his filament-level attention to the nature of our collective emotions, fears, and social anxieties, he ultimately lands on the familiar — and tedious — assertion that Trump supporters are the way they are because they simply weren’t understood well enough by people who questioned unchecked capitalism, overt racism, and an ethos, such as it is, of fuck your feelings. Edmundson invites us to take whatever empathy the internet hasn’t scoured out of our souls and consider a neighbor of his, a guy who likes to “think things through for himself.” Edmundson’s portrait of this neighbor’s grievances is worth quoting at length:

“Liberals are trying to tell my neighbor what to do on an ethical level. They’re trying to boss him around. They have opinions about what he ought to say and what he ought to eat and the vehicle he ought to drive and the way he ought to regard the other gender (or genders). They want him to avoid one set of words and embrace another set. And the words, proscribed and endorsed, seem to change every week. They want to mess with basic bathroom protocols. They want to outlaw jokes. They aspire to get in his head and judge him nonstop.”

Leftist scolds, in short, are the super-ego incarnate: They boss and bully and lecture and judge. On the flipside, liberals don’t face a similar “oppression” from the right; rather, the oppression is self-generated. Liberals are beaten down by the internet, which tells them who’s in and who’s out, delivers absolutist diktats about right and wrong. Externally, they take all this out on the right. Internally, they become overly obsessed with identity — overly, in this context, because identity presumes a wholly resolved sense of self that Freud believed was impossible. Edmundson’s conclusion from this is that anyone concerned about identity is psychically locked in neutral, raging at others rather than bettering themselves. “Identity is not enough,” Edmundson writes. “To put the matter crudely, once one decides who one is, one must decide what one will do.”

Leftist scolds, in short, are the super-ego incarnate: They boss and bully and lecture and judge. On the flipside, liberals don’t face a similar “oppression” from the right; rather, the oppression is self-generated. Liberals are beaten down by the internet, which tells them who’s in and who’s out, delivers absolutist diktats about right and wrong. Externally, they take all this out on the right. Internally, they become overly obsessed with identity — overly, in this context, because identity presumes a wholly resolved sense of self that Freud believed was impossible. Edmundson’s conclusion from this is that anyone concerned about identity is psychically locked in neutral, raging at others rather than bettering themselves. “Identity is not enough,” Edmundson writes. “To put the matter crudely, once one decides who one is, one must decide what one will do.”

It’s not clear why Edmundson presumes that they don’t, or won’t make that decision. Since the subject of his attention is often the (lefty) students he teaches, it may be that they legitimately haven’t made that decision yet. Edmundson sees a super-ego-driven crisis here. But he doesn’t bother to explore the fairly obvious point that discussions about identity aren’t about making identity an end in itself but a means of supporting the idea that people can do what they wish to do without being held back because of that identity. Nor does he explore why this purported super-ego problem is unique to the internet age. Cultures arranging themselves around belonging — sometimes violently so — have existed for millennia. Blacks, Asians, Jews, and women have been well aware of the contempt they faced well before they had DM for bigots to slide into. Nazis didn’t need 4chan to discuss their horrors.

Edmundson is a valuable writer, for decades a prominent voice defending the humanities in an era when such figures have been lamentably thin on the ground. He wishes we wouldn’t be so easily swayed by the idiot winds of trends. Me too; he’s not wrong to point out that the internet can accelerate idiocy to gale-force levels. Internet mobs have needlessly thrust the lives of many people into crisis; social media has made flirting with fascism an easy game to play. But there’s little in Edmundson’s book to suggest that the internet era is worse on this front than any other era — except that it plays into Edmundson’s conclusion that we’ve lost touch with some core principles of civilization, the stuff of Jesus and Homer and Socrates. Toward the end of the book, he riffs on “the pursuit of wisdom, the pursuit of bravery, and the pursuit of compassion” as if they are now lost causes, and proposes a few ways we might more effectively get in touch with such things: tell jokes, drink a little, look into religion, or therapy. As suggestions, they’re better than nothing. But as history it elides a couple thousand years of ever-vacillating comfort and distaste with mob rule and institutionalized cruelty. And as self-help, it’s pretty feeble, a mix of glib Stoicism-lite and Jordan Peterson-style sophistry.

Edmundson is a valuable writer, for decades a prominent voice defending the humanities in an era when such figures have been lamentably thin on the ground. He wishes we wouldn’t be so easily swayed by the idiot winds of trends. Me too; he’s not wrong to point out that the internet can accelerate idiocy to gale-force levels. Internet mobs have needlessly thrust the lives of many people into crisis; social media has made flirting with fascism an easy game to play. But there’s little in Edmundson’s book to suggest that the internet era is worse on this front than any other era — except that it plays into Edmundson’s conclusion that we’ve lost touch with some core principles of civilization, the stuff of Jesus and Homer and Socrates. Toward the end of the book, he riffs on “the pursuit of wisdom, the pursuit of bravery, and the pursuit of compassion” as if they are now lost causes, and proposes a few ways we might more effectively get in touch with such things: tell jokes, drink a little, look into religion, or therapy. As suggestions, they’re better than nothing. But as history it elides a couple thousand years of ever-vacillating comfort and distaste with mob rule and institutionalized cruelty. And as self-help, it’s pretty feeble, a mix of glib Stoicism-lite and Jordan Peterson-style sophistry.

No doubt, we’d do well to better acknowledge our super-ego, that supercilious jackass in our heads. Our internal critical voice can overwhelm us. Acknowledging that voice may also help direct us, but Edmundson feels our chief job as regards the super-ego is to quiet it, through wisdom, bravery, compassion, etc. “One overcomes the super-ego not by civilizing it, not by turning it into an ego-idea, not by entering into a dialogue with it,” he writes. “One displaces the super-ego by going above it.” As bucket-list goals go, denying a defining aspect of our psyche is … ambitious. Perhaps the goal should be less about denial and more about social awareness. And an acknowledgment that while a Twitter pile-on is many things, rarely is it oppression or evidence of a cultural psychotic break.

[Published by Yale University Press on April 25, 2023, 192 pp., $26 hardback.]