Marilyn Hacker and Ellen Bryant Voigt both began publishing in the mid-1970s. Hacker’s debut collection, Presentation Piece, arrived in 1974; Voigt’s first volume, Claiming Kin, was issued in 1976. This was not the most exciting decade in American poetry. The period style had become a watered-down admixture of over-sharing personal history, mild-mannered surrealism, and the I-do-this-I-do-that list-making of the New York School, most of it offered in a free verse that had been stripped of any of its capacity for invention or surprise: short lines, few enjambments, stultifyingly simple syntax. Hacker and Voigt’s first books departed significantly from this norm, Hacker’s through a pyrotechnical swagger that often incorporated demanding received forms such as the canzone and the sestina, and Voigt through a quiet acuity of seeing and a concern for narrative that owed a debt to Elizabeth Bishop, a poet who in those days was not exactly fashionable.

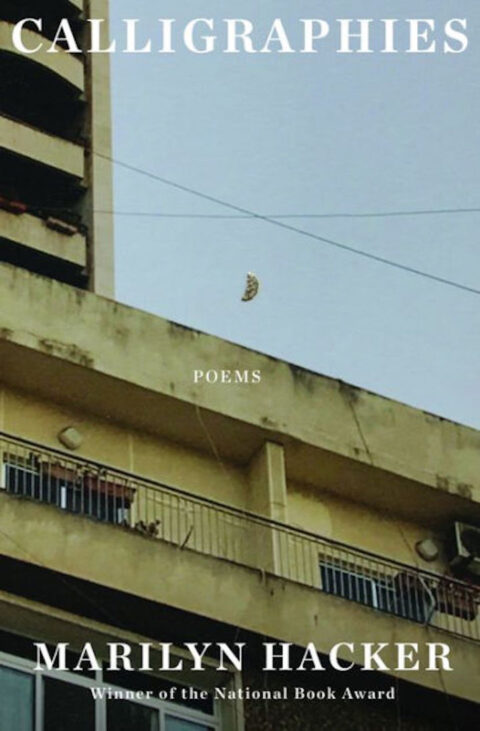

Both poets, through their efforts to address the stylistic limitations of the period style, were seen by readers as “formalists,” a label that in 1970s-speak was more than a little pejorative. This bit of othering was not an obstacle for the pair. Both went on to distinguished careers, and both have been prolific: Calligraphies is Hacker’s seventeenth individual collection; Voigt’s Collected Poems is a hefty 500 pages. Readers probably still regard the pair as formalists, a descriptor that is, fortunately, no longer a diss. But it is also a reductive label; better to consider them formalists-with-an-asterisk.

Both poets, through their efforts to address the stylistic limitations of the period style, were seen by readers as “formalists,” a label that in 1970s-speak was more than a little pejorative. This bit of othering was not an obstacle for the pair. Both went on to distinguished careers, and both have been prolific: Calligraphies is Hacker’s seventeenth individual collection; Voigt’s Collected Poems is a hefty 500 pages. Readers probably still regard the pair as formalists, a descriptor that is, fortunately, no longer a diss. But it is also a reductive label; better to consider them formalists-with-an-asterisk.

Although the pair differ from one another in their concerns and methods, they share a durable — and sometimes quirky — mastery of prosody that is unmatched in contemporary verse. But it’s not their technique alone that instructs us: both writers have continued to evolve and to deepen their expressive range. Hacker is among that especially noteworthy company of artists who in late career eschew the virtuoso displays that marked their early work, replacing them with a grave minimalism, with a style more interested in imparting world weary wisdom than in exercising one’s chops: late Milosz comes to mind here, as does late Bob Dylan. Voigt’s most recent work also departs from the approach that made her reputation. Headwaters, the last volume to be published before her Collected, replaces the lapidary stanzas and periodic sentences of her signature style with unpunctuated poems in long Whitmanic lines, most of them enjambed; the poems are imbued with an associational vigor that deepens Voigt’s already formidable powers of observation.

To fully appreciate the lean and mean authority of Hacker’s recent work, it’s helpful to contrast it with the glitter and panache of her early poems, those represented in her Selected Poems 1965-1990 and in a wildly bravura novel-in-verse, Love, Death, and the Changing of the Seasons. This is the period that caused J.D. McClatchy, a critic better known for withering putdowns than for praise, to label Hacker as “our latter-day Bryon.” McClatchy’s label isn’t as hyperbolic as it sounds, given the early poems’ combination of cosmopolitan wit, canny self-portraiture, Sapphic ardor, political savvy, and of course their prosodic Midas touch. As with Byron, her brand of Romanticism isn’t much interested in apotheosizing Nature: instead, people are her thing. She loves writing verse epistles filled with snappy reportage, sly character studies, and a tone that can suddenly veer from whimsy to pathos. The poems are not akin to letters, they are letters, scrupulous in their desire to entertain and inform her correspondents, be they Hacker’s daughter, her lovers, or any number of fellow poets. The fact that these letters come to us in sapphics, as sonnet crowns, as sestinas, as pantoums and in terza rima seems almost beside the point. Consider this section from Love, Death, and the Changing of the Seasons.

To fully appreciate the lean and mean authority of Hacker’s recent work, it’s helpful to contrast it with the glitter and panache of her early poems, those represented in her Selected Poems 1965-1990 and in a wildly bravura novel-in-verse, Love, Death, and the Changing of the Seasons. This is the period that caused J.D. McClatchy, a critic better known for withering putdowns than for praise, to label Hacker as “our latter-day Bryon.” McClatchy’s label isn’t as hyperbolic as it sounds, given the early poems’ combination of cosmopolitan wit, canny self-portraiture, Sapphic ardor, political savvy, and of course their prosodic Midas touch. As with Byron, her brand of Romanticism isn’t much interested in apotheosizing Nature: instead, people are her thing. She loves writing verse epistles filled with snappy reportage, sly character studies, and a tone that can suddenly veer from whimsy to pathos. The poems are not akin to letters, they are letters, scrupulous in their desire to entertain and inform her correspondents, be they Hacker’s daughter, her lovers, or any number of fellow poets. The fact that these letters come to us in sapphics, as sonnet crowns, as sestinas, as pantoums and in terza rima seems almost beside the point. Consider this section from Love, Death, and the Changing of the Seasons.

Lacoste IV

It’s almost as if we’re already there

in the narrow stone house, me upstairs

writing on the splintery pine table,

you in the downstairs study, with its cradle

of a marriage bed, slit window looking

into the Buniols’ herb garden. I’m cooking

a sonnet sequence and a cassoulet

with goose from Carcassone, let mijoter

on the burner till nightfall. The vow

of silence breaks at seven. It’s noon now.

Pleasure delayed is pleasure amplified —

I’ll show you these bitch Welsh quatrains I’ve tried.

It’s your turn to work outdoors in the sun

on the roof — your footsteps, and the last line’s done.

The premise here is quite straightforward: here’s my fantasy of our summer rental in the south of France. Yet it’s offered with a cinematic particularity, and a coy erotic charge. The couplets are effortless, even when they turn bilingual. And the poem is also effortless in the way that it morphs from fantasy to ars poetica. Cooking up the cassoulet and concocting the sonnet sequence become one and the same, and both are a form of foreplay. But Hacker’s wit and masterly technique could be put to other uses. “Untoward Occurrence at the Embassy Poetry Reading,” from Presentation Piece, is a consummately clever political allegory in the manner of 1930s Auden. It’s culture night at an American embassy in an unnamed country, and the poet giving the reading is its speaker, who initially comes off as just another dreary academic on a Fulbright. But as the poem unfolds, she turns out to be a guerilla leader, whose minions have taken over the embassy:

Tomorrow, foreigners will read

rumors in newspapers … Oh, Sir, your death

would be a tiresome journalistic subject,

so stay still till we’re done. This is our season.

The building is surrounded. No more poetry

tonight. We’re discussing, you’ll be pleased

to know, the terms of your release. Please read

these leaflets. Not poetry. You’re bored to death

with politics, but that’s the season’s subject.

And, yes, the poem also happens to be a sestina, featuring a pretty cheeky mix of end words.

With 1996’s Winter Numbers, Hacker’s work significantly changes: the poems begin to favor reflection over immediacy, and not simply because she had become a writer-of-a-certain- age. A more complicated confluence of factors is responsible for this later mode, one that Hacker continues to refine in Calligraphies. As her correspondents pass away, elegies become as common as her verse epistles. The poet herself confronts mortality and aging, as evidenced by a harrowing sequence entitled “Cancer Winter.” Hacker’s status as an expatriate — she has lived in France for several decades — also informs the poems, imbuing them with an intricately layered sense of outsiderhood — a mixture of melancholy and acuity of the sort one that one also sees in Bishop’s Brazilian writing, or in the later poems of Hacker’s fellow Parisian expat, C. K. Williams. Yet the prevailing focus of Hacker’s most recent work derives from her travels to the Middle East, her translations of modern Arabic poetry, and her championing of human rights within the Arab world — and especially within its various exile communities. This immersion has correspondingly affected the forms Hacker employs. Her dexterity with the sonnet is abundantly on display in Calligraphies, but she is now equally engaged by non-Western forms such as the ghazal and the pantoum.

But the mode which predominates in Calligraphies is Hacker’s unique variant on the renga, a Japanese syllabic form that is frequently employed in literary collaborations: traditionally, the authors of a renga write poems in alternation, with each new section responding to the poem by the previous writer. In recent years, Hacker has co-authored two such partnerships, one with Palestinian American poet Deema Shehabi, entitled Diaspo/Renga, and another with French-Indian poet Karthika Nair, called A Different Distance. Hacker’s “Calligraphies” is a sequence of 12 “solo” rengas, all of them multi-sectioned, all of them several pages in length. Each section within the rengas is 10 lines long, and combines a pair of tankas: the section’s final line is echoed in the first line of the next. A lot like a sonnet crown in other words, but a crown that has been chopped and channeled, with its sections half-erased, proceeding through association rather than narrative, filled with fragments, notations, fleeting perceptions and memories aplenty, many of them intrusive rather than nostalgic. This pair of sections, drawn from “Calligraphies IV,” will give you a sample of the method’s flavor.

But the mode which predominates in Calligraphies is Hacker’s unique variant on the renga, a Japanese syllabic form that is frequently employed in literary collaborations: traditionally, the authors of a renga write poems in alternation, with each new section responding to the poem by the previous writer. In recent years, Hacker has co-authored two such partnerships, one with Palestinian American poet Deema Shehabi, entitled Diaspo/Renga, and another with French-Indian poet Karthika Nair, called A Different Distance. Hacker’s “Calligraphies” is a sequence of 12 “solo” rengas, all of them multi-sectioned, all of them several pages in length. Each section within the rengas is 10 lines long, and combines a pair of tankas: the section’s final line is echoed in the first line of the next. A lot like a sonnet crown in other words, but a crown that has been chopped and channeled, with its sections half-erased, proceeding through association rather than narrative, filled with fragments, notations, fleeting perceptions and memories aplenty, many of them intrusive rather than nostalgic. This pair of sections, drawn from “Calligraphies IV,” will give you a sample of the method’s flavor.

Eight in the morning.

The old woman down the hall

is playing Fairouz.

Gray rain stains these slanted roofs.

Beirut smothers in sandstorms.

The drunkard implores

his neighbor’s pretty daughter

not to forget him

in the grand old woman’s song.

Down the hall, she sings along.

**

A hall of closed doors

locked on possibilities,

a hall of mirrors,

each reflection is grotesque.

Frontiers are rediscovered

and fenced with barbed wire.

My grandfather’s language and

the one I plug at

shouted at each other, un-

comprehending. Mirrors, doors.

This passage also suggests the prevailing theme of the “Calligraphies” sequence. Again and again, Hacker laments the struggle with “language … uncomprehending,” with language’s debasement through cant, inexactitude, and oppression. And Hacker, for all of her polyglot fluency and technical skill, for all of the intimacy she brings to her poems and their addressees, finds this task increasingly daunting and bewildering. Although her goal is to move toward what Celan so memorably called “an addressable Thou, an addressable reality,” that goal grows more elusive as the poet reckons with the covid pandemic, the discomforts of aging, and what one poem calls, “political grief,/apolitical despair,/ and it’s vice versa.” Hacker’s signature wit still informs the poems, but it is now more rueful and fraught. Consider the closing section of “Calligraphies VIII.” “N” — presumably Hacker’s fellow poet Karthika Nair — addresses a scathing comment to her. Hacker’s rejoinder is quietly majestic:

When N. said to me,

frank, not sad, “I don’t know you,

and you don’t know me.”

We talk in a language that’s

not my mother tongue or yours.”

I was standing at

the counter with a wineglass,

dicing aubergines,

while she sat at my kitchen

table, and drank the same wine.

In the closing pages of the collection, Hacker returns to her formal home-place, offering a series of sonnet crowns that remind us — not that we needed such reminding — that her facility with the form is rarely short of astounding. But Hacker never settles for the easy tour-de-force. The sonnet is second nature to her, comfortable as a favored robe or cherished jacket, and a talisman to ward off heartbreak. The spirit of the closing sequences, written during the covid lockdown and its aftermath, is elegiac but not bereft. This section from “Montpeyrouk Sonnets 4” mourns Hacker’s friend Fadwa Soliman, a prominent activist in the Syrian rebellion against the Assad regime:

A breath of winter silence at the door

that doesn’t open for someone who kneels

sheds her, his shoes on the runner. Time unreels,

doesn’t rewind. Fadwa died young, four

years ago. She isn’t anywhere,

least in a cemetery in Montreuil,

exiled from all she never got to say

in either language. The second plague year.

I’m still alive, still vulnerable, older

than when we walked from Bastille to Concorde

and back, recounting, sparring, every word

glistening with possibility. It’s winter,

darkening. I take a letter from the folder,

put it back. The door’ shut. They won’t re-enter.

Note the self-consciously ambiguous pronoun in the final line. Hacker’s “they” could have several referents — the various “someone”s who appear at the writer’s door, or her friend Fadwa, or the words that once “glistened with possibility.” Each likelihood is suffused with lament. Yet Hacker’s abjection is counteracted in the poem’s most memorable line: “I’m still alive, still vulnerable, older.” The line is so blunt that it takes us some time to recognize its artfulness: the unobtrusive consonance of the “l”s, and the melodic flow of four iambs brought to a decisive halt thanks to that comma — followed by the gruff trochee of “older.” This sonnet deftly encapsulates the combination of sturdiness and fluency that makes Hacker’s late work so haunting and so memorable.

*

Hacker is very much an urban poet. Voigt, by contrast, aligns herself firmly within the pastoral tradition, following in a direct line behind the likes of Virgil, Clare, Edward Thomas, and especially the darker side of Frost. Like them, she doesn’t apotheosize nature. She knows all too well the travails and tedium of rural life, but also knows its consolations. Fittingly, she is also a regionalist. Raised in Western Virginia, she is a Southern writer through and through, though not in the masculinist tradition of Fugitives and Faulknerians. Her touchstones seem to instead be that small coterie of the last century’s Southern women poets, figures such as Betty Adcock and the criminally undervalued Eleanor Ross Taylor, writers who quietly but pointedly sought to undermine Good Old Boy bombast. The fact that Voigt left the South long ago, and has lived in rural Vermont for almost half a century, has not diminished her desire to reckon with Southern culture’s manifold injustices and ambivalent charms. The South is for Voigt a realm of fraught recollection, of Proustian reveries whiplashing to troubled reckonings. Consider “At the Movie: Virginia, 1956,” from Voigt’s third collection, The Lotus Flowers, a withering depiction of the casual barbarity of segregation and the stultifying conventions of a small Southern town. Jim Crow is practiced “like a chivalric code/laced with milk,” The speaker’s recognition of its perniciousness comes during a Saturday matinee, where whites occupy the main floor, and blacks the balcony. Here’s the poem’s ending:

By then I was thirteen,

and no longer went to movies to see movi

The downstairs forged its attentions forward,

toward the lit horizon, but leaning a little

to one side or the other, arranging the pairs

that would own the county, stores and farms, everything

but easy passage out of there —

and through my wing-tipped glasses the balcony

took on a sullen glamor: whenever the film

sputtered on the reel, whenever the music died

and the lights came on, I swiveled my face

up to where they whooped and swore …

wanting to look, not knowing how to see,

I thought it was a special privilege

to enter the side door, climb the stairs

and scan the even rows below — trained bears

in a pit, herded by the stringent rule,

while they were free, lounging above us,

their laughter pelting down on us like trash.

Many of the benchmarks of Voigt’s mature style are present here: the skill with narrative, the elegantly managed free verse that leans toward pentameter, and a highly engaging command of syntax: the last sentence I’ve quoted goes on for seventeen lines, yet the passage never seems laborious. The tone is quietly commanding, with the carefully modulated descriptions suddenly giving way to the acrid shock of the four closing lines. It’s a method ideally suited for capturing the workings of memory, for offering clean, unsentimental portraiture — especially of Voigt’s parents, who are the subject of many of her poems — and for evoking, also unsentimentally, the cycles of a bygone rural life.

The poems which derive from Voigt’s life in New England are of another sort entirely, but they locate themselves just as squarely within the pastoral. The poems tend to eschew narrative for a lyric immediacy; they are apt to be shorter, more associative, less adorned. They often focus on domestic life — she has some affecting, unfussy poems about parenting, and a number of similarly canny love poems — yet they take startling turns. “Practice,” from 2002’s Shadow of Heaven, deserves to be quoted in full:

To weep unbidden, to wake

at night in order to weep, to wait

for the whisker on the face of the clock

to twitch again, moving

the dumb day forward —

is this merely practice?

Some believe in heaven,

some in rest. We’ll float

you said. Afterward

we’ll float between two worlds.

Five bronze beetles,

stacked like spoons in one

peony blossom, drugged by lust:

if I came back as a bird,

I’d remember that —

until everyone we love

is safe is what you said.

Waking in the middle of the night to brood on mortality: it’s a familiar lyric subgenre. Yet Voigt evokes the experience with a disquieting acuity and economy. The repetitions and enjambments give the opening stanza a propulsive movement and a visceral sense of the speaker’s dread. And the speaker isn’t buying the fuzzy version of the afterlife that the “you” of the poem has offered her, try though she might. But then we’re given the poem’s remarkable third stanza; it comes without warning, an epiphany — an inscape! — of the sort you’d find in Hopkins. And it should be noted that the poem is something like a sonnet, much in the way that the sections of Hacker’s rengas are.

Voigt has given us variations on these two kinds of poems—the North Poems and the South Poems, if you will–throughout her career, and she is careful to structure her collections so that the two approaches compliment and complicate one another. But two of her volumes, and they’re perhaps her most distinguished ones, are outliers. I’ve already mentioned 2013’s Headwaters, with its long unpunctuated lines that unfold at a dizzying pace, stream of consciousness poems where narrative and lyric uneasily commingle Here’s a representative sample, the opening of a poem entitled “Stone”: “birds not so much the ducks and geese ok not horses cows pigs/she’d lived in the city all her life some cats and dogs ok as part/of someone else’s narrative …” Headwaters is an admirable experiment, a late career stylistic change that shows the writer finding new ways to exercise her considerable gifts. But I think 1995’s Kyrie, a book-length suite of sonnets set during the 1918 influenza pandemic, is the collection for which Voigt will be best remembered. The book is quite a formal tour de force, with “strict” sonnets employing end rhyme and pentameter alternating with more loose and idiosyncratic ones. Yet Voigt’s facility with the form seems almost beside the point: we’re drawn instead to the plights of the dizzyingly large cast of characters Voigt introduces: some are evoked in capsule portraits, some through dramatic monologues; some survive the pandemic, but most do not; some recount their suffrings with a stoic terseness; others rail at God. They’re ordinary folk, most of them rural. Voigt weaves in period details, never heavy-handedly. She offers up a handful of documentary sections which place the poems in their historical context, but not many. It’s the lost and ruined lives that matter to Voigt. Here’s a representative section:

Voigt has given us variations on these two kinds of poems—the North Poems and the South Poems, if you will–throughout her career, and she is careful to structure her collections so that the two approaches compliment and complicate one another. But two of her volumes, and they’re perhaps her most distinguished ones, are outliers. I’ve already mentioned 2013’s Headwaters, with its long unpunctuated lines that unfold at a dizzying pace, stream of consciousness poems where narrative and lyric uneasily commingle Here’s a representative sample, the opening of a poem entitled “Stone”: “birds not so much the ducks and geese ok not horses cows pigs/she’d lived in the city all her life some cats and dogs ok as part/of someone else’s narrative …” Headwaters is an admirable experiment, a late career stylistic change that shows the writer finding new ways to exercise her considerable gifts. But I think 1995’s Kyrie, a book-length suite of sonnets set during the 1918 influenza pandemic, is the collection for which Voigt will be best remembered. The book is quite a formal tour de force, with “strict” sonnets employing end rhyme and pentameter alternating with more loose and idiosyncratic ones. Yet Voigt’s facility with the form seems almost beside the point: we’re drawn instead to the plights of the dizzyingly large cast of characters Voigt introduces: some are evoked in capsule portraits, some through dramatic monologues; some survive the pandemic, but most do not; some recount their suffrings with a stoic terseness; others rail at God. They’re ordinary folk, most of them rural. Voigt weaves in period details, never heavy-handedly. She offers up a handful of documentary sections which place the poems in their historical context, but not many. It’s the lost and ruined lives that matter to Voigt. Here’s a representative section:

How we survived: we locked the doors

and let nobody in. Each night we sang.

Ate only bread in a bowl of buttermilk.

Boiled the drinking water from the well,

clipped our hair to the scalp, slept in steam.

Rubbed our chests with camphor, backs

with mustard, legs and thighs with fatback

and buried the rind. Since we had no lambs

I cut the cat’s throat, X-ed the door

and put the carcass out to draw the flies.

I raised the upstairs window and watched them go —

swollen, shiny backed, green-backed, green-eyed —

fleeing the house, taking the sickness with them.

I’ll let this poem speak for itself. I’d need to quote from a score or more of poems in order to suggest something of Kyrie’s cadences, or its play of leitmotifs, or the cumulative effect of its threnody.

In “Under Ben Bulben,” Yeats’ purported last poem, before he so grandly eulogizes himself, he offers sixteen lines of admonishment to the poets who will come after him. Most of his counsel is Yeatsian mumbo-jumbo, but the core advice is not: “Irish poets, learn your trade.” By “trade,” Yeats means what we would call “craft.” I don’t think Hacker or Voigt are prepared to offer parting advice to the generations of poets who follow them, and I’m eager to see how their late-career flowering will continue. But if — from the perspective of their commendable bodies of work — they were willing to give the rest of us a tip or two, I suspect that it would come in the form of something like “learn your trade.” And they, of course, have learned the trade supremely well.

[Calligraphies by Marilyn Hacker, published by W. W. Norton on April 4, 2023, 144 pages, $26.95 hardcover; Collected Poems by Ellen Bryant Voigt, published by W. W. Norton on February 21, 2023, 496 pages, $30.00 hardcover]

Brilliant, and a pleasure to read, as always.