Map for a (New) World

1.

I am thinking about maps.

As of today, I have been inside — locked down, sheltering, whatever you want to call it—for ten months. Four months in Montevideo, Uruguay, then, after a mad, masked flight, for another six months in Madison, Wisconsin. I am not thinking about taking out the official State of Wisconsin road map or the route maps in the back of inflight magazines, but rather the maps we hold in our bodies, our memories. Maps of routes we can walk in our minds even when, mid-pandemic, we cannot leave our houses.

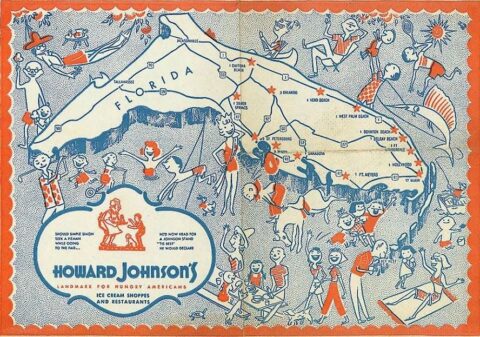

I have also been drawing every day, something new for me. I feel I should be able to draw a map of where I am, of where we are. But I don’t know what it should look like. Maybe it should resemble the placemats from Howard Johnson’s in my Florida childhood where it wasn’t roads that were important, but the men and women and children who were so clearly having fun.

But are we having fun?

Instead of a map, I draw this —

2.

I am thinking about maps.

But I still can’t seem to draw one.

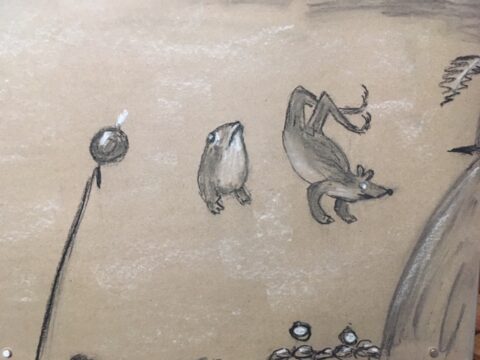

My current drawing obsession is charcoal sketches based on the random bits of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights sent out into the world by the Boschbot. Several times a day, the bot tweets close ups of this large triptych, perhaps part of some fantastic animal, naked human or burning building. Or a hand entering the frame from one corner, reaching for something that isn’t there. Or a pair of feet standing on empty grass.

My obsession isn’t really with Hieronymus Bosch or even this particular painting. What fascinates me is how I can’t see the complete image at any time, how I am always guessing/grasping at connections. This incoherence seems to fit with this plague year when none of us can see the whole. Like a jigsaw puzzle, if I put enough pieces together, will they somehow show me the way? Will my drawings become a map?

But I draw one and think — how is this part of any sensible map?

Then again, maybe a sensible map is not what we need.

3.

I am thinking about maps.

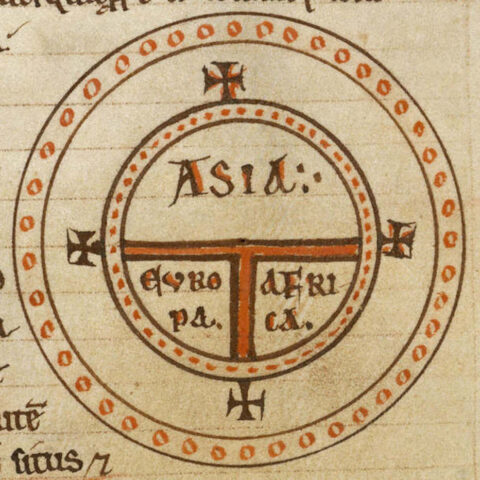

I am wondering what a map of the circle of houses where I lived as a kid in Cocoa, Florida would look like. My house was 3089 Sunset Terrace, then around the circle, in order, the houses of my friends: Kathy Worley, Lisa Hall, Patty Semine. I think it would look like a medieval T and O map, an orbis terrarum, circle of the lands, a map of the world with Jerusalem always in the center.

Each cross on the map would be one of our houses, mine at the bottom. Patty, my best friend, at the top.

Then, when I was 11, Patty moved away—to Michigan. At that age, in those days, to have a friend move away was like having a city erased from the map, cease to exist, like Pompeii after Vesuvius erupted, all life buried from sight. Another family moved into her house—but with no children my age—and it was never the Semine’s again. It became a house that wasn’t worth putting on any map of mine.

Instead of a map, I pick this tweet from the Boschbot to draw:

Maybe Patty — being snatched from my life?

4.

Right now, though I am back in my house in Madison, Wisconsin, I can close my eyes and see the view out my living room window of my 7th floor apartment in Montevideo, Uruguay, a city I love, a city where I have spent a lot of time. I make a mental map:

A. First Bulevar España. A four lane, usually very busy street — cars, buses — that is, during the lockdown, suddenly completely still.

B. Then across Bulevar España, on the right, is a curved, 1920s art deco apartment building with balconies, one of which is the home of a dog whose barks are so constant and loud they take the place of the traffic noise that used to fill the street. On the left, a pet food store where I went on the last day of an American friend’s visit helping her buy cat toys. Then she and her husband flew back to the U.S. Then the planes stopped. And the cars.

C. Between the two buildings is the cross street, Joaquin de Salterain. My address is Salterain 1501. But if you look up that address on Google maps, it will tell you that address is on the far side of Bulevar España, in the Art Deco building with the barking balcony dog. The system for numbering buildings in Montevideo defies the logic of Google maps.

D. If I look down Salterain, I see three-story houses, painted the pale beige or white or tan that is most common here. Bright colors are rare. To be honest, Montevideo is a city built of concrete, the color of concrete. I once told an Uruguayan friend my house in Wisconsin was blue and he said, Why? I told another friend my house in Wisconsin was made of wood and she said, Is that safe?

E. If I walk down Salterain, cross the park, I would arrive at the sea. Except it is not the sea, really. It is the broad mouth of the Río de la Plata, the brackish water estuary too wide to see across, though if you could, Argentina would be to your right, and tucked further up the river. Straight ahead though—nothing but water until Antartica.

Taking that walk in my imagination is like drawing a map — a lovely map.

But the truth is, I do not really want to walk as far as the sea. If this were before March 13 when the pandemic arrived in Uruguay, I would walk one block down Salterain, turn right on Calle Durazno (Peach Street!), then left on Pablo de Maria, and ring the doorbell at 1040 Pablo de Maria where my friend Leticia lives. She would come down the stairs to open the door we would kiss each other on the cheek and climb back up the marble stairs to her apartment where we would have tea and talk. I cannot do this now — even if I were still in Montevideo, I could not. And that is the real sorrow.

How do I draw a map of being alone?

I draw this.

Is it a map?

5.

I am still thinking about maps.

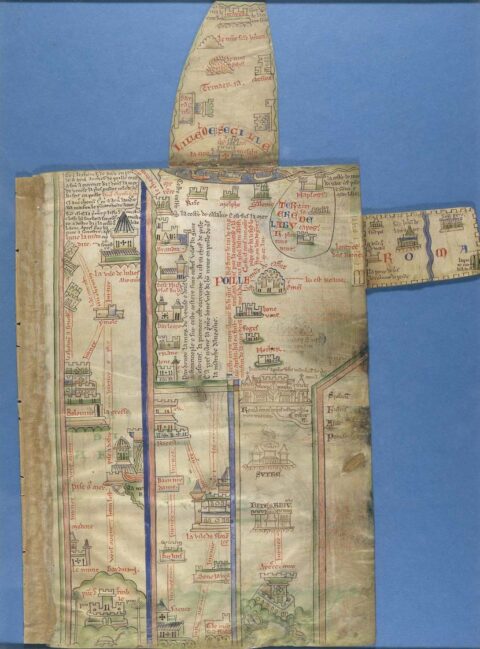

This time about the medieval pilgrim map. More particularly about a map by the medieval monk Matthew Paris or Matthew of Paris (c. 1200–1260). I have been looking at his map, in his chronicle of world history, Chronica Major, that shows the route from London to Jerusalem. It is a kind of medieval road map spread over seven pages that takes the viewer on a pilgrimage from London to Rome and Jerusalem.

The British Library says Matthew entered the Abbey of St Alban on January 12, 1217, and spent the rest of his life there, apart from a year-long mission that took him to an abbey in Norway. But the Library says, “Through the maps that he created, however, he travelled the world.” And all his maps “are marked by his intense curiosity about the outside world; he experiments with different renderings as if trying to work out his own ideas of what the world was really like.” Like me, sitting at my desk, but still wanting to travel, at least in my imagination.

Looking at the map, it seems very practical. Rivers, hills and important buildings are shown clearly along the way. His routes are straight lines with all the extra information that a pilgrim would have needed or he found interesting written in on the side — half guide book, half personal (though imaginary) journal. He adorns his map with drawings of buildings and towns and quite often with additional decoration. Once in Palestine, palm trees and camels — things he could never have personally seen — appear. Like the leaping swordfish drawn as embellishment in the blue margins of the Howard Johnson’s map of Florida.

The British Library speculates that, perhaps, the map “represents a spiritual rather than a physical journey. Each place on the journey probably had its allegorical counterpart within the cloisters and church of St Albans Abbey (rather like the Stations of the Cross in modern Catholic churches) and the monks would follow the route as a type of spiritual exercise.”

So his map, it seems to me, is very like my mental maps, drawn so I can take imaginary journeys in a time when my world is as limited as Matthew of Paris’s—ones that let imagination and image open a window to the world I know is still out there.

I study Matthew of Paris’s map and think surely I could draw one like his, but today what I drew was this.

Jerusalem? Or the Gates of Hell? Because it is Bosch, I am pretty sure it is the latter.

6.

I can’t stop thinking about maps.

Although Montevideo is a city of a million and a half people, on lock-down it shrank to a mental map to my friends’ houses. Just a bit further than my friend Leticia’s house was the house of my other dear friend in Montevideo, Silvia. For most of her adult life, while she raised three children, she lived just off Bulevar España. To go to her house, I would just walk down hill, and turn left onto the small block-long street where she lived. I could close my eyes and imagine a circle map that would include only three crosses, one for my house, one for Leticia’s and one for Silvia’s, replicating the small world of my Florida childhood.

But Silvia had to move, suddenly, distressingly. She’d been raised in the beach town of Maldonado, about two hours north of Montevideo, where the sea really is the wide, cold Atlantic. She still owns her mother’s house there which she had tried to keep rented. I had stayed there, walked to the wide sand beach to swim. But when the pandemic brought financial collapse to many parts of the Uruguayan economy. she couldn’t rent her mother’s house. Instead, she got an offer to rent her house in Montevideo. So in mere days, she had to pack the furniture and books and goods of a life time and move to back Maldonado. Someone else, a stranger, is in her house now. So, like Patty Semine’s house, it is no longer on my imaginary map. It is not Silvia’s house to me anymore.

But unlike 11-year old Patty, Silvia has not disappeared from my life. I talk to her on WhatsApp and we send messages and photos back and forth. When I was in Uruguay, Leticia, too, was still there for me to talk to, on Whatsapp, on Skype. She is still there, though we are 6000 miles and two time zones apart. My other friends in Montevideo during lockdown were not more or less available by distance but by their use of technology. Javier’s apartment might be a long bus ride to Malvin, but he was a just Whatsapp message away.

Now that I am back in Madison, my husband and I walk every morning. We start at our house and walk a perimeter of a dozen blocks in our neighborhood, over the narrow Yahara River and back. We have become quite observant, noticing over the summer every new garden, all the changes people made to their porches and yards because their lives were entirely lived at home now. Then came fall. The Jack o’ Lanterns for Halloween, our neighborhood’s favorite holiday. Winter. Christmas decorations. Snow. The lake freezing. The river rimmed with ice. This morning, when we walked, we noticed all the rime ice covering the trees along our way.

I could draw a map of our route from memory — put in, say, each purple house (we pass four). Or each house with a tower (we pass six). Or the doors of houses of people I know. But their houses are just landmarks, like the purple houses, towers, the small arched bridge over the river. The idea of a friend’s house being a destination, a place where I could visit the humans inside, has come unstuck, undone, unreal.

But this morning, I will see one group of friends for a writing session on Zoom. Then, in the afternoon, I am taking an art lesson on Facetime. I am not sure how to map these places except on my Google calendar with links to the online sessions, as events in time — but not space. Is my calendar my only map now?

Today, I will also email with friends, message with friends — some in the same town. Others in other cities, states, countries. Before, when I did this, I thought of them physically placed on a map, I knew it would take a four hours drive to see one or an overnight flight to Montevideo or Japan see another. But now, I don’t. I am here. They are there. But the distance between “here” and “there” has changed to the speed of our internet connection. They are also here. In my house. Or some electronic reflection of them is.

I have begun to think of these friends as stars in the galaxy. Over Christmas I watched It’s A Wonderful Life with my 22-year old son who had somehow never seen it. I had totally forgotten the opening where God and the various angels are white stars in a B & W sky that pulse when they talk to each other.

Like that, I thought, my friends these days are like that. Bright lights, I can see and hear. Beyond the points of the friends I talk to regularly, lie the scattered stars of further galaxies, of the Facebook friends, of the people I’ve come to know on Twitter or Instagram. But there are no roads in the physical world that run from where I am to where they are.

So maybe the only possible map of the virtual friend universe is a star map. And it is up to me whether to see all those points of light as brilliant — or distant and cold.

So today, I drew stars.

7.

I am thinking about what happens when you walk off the edge of the map.

Yesterday, I walked out on a frozen lake and felt like Jesus walking on the water.

It is always a shock, a shift in perspective. You stand on the ice looking back at the houses on the shore, their docks, their boat houses. Clearly that is the real world. But you are someplace purer, whiter.

After that, I had a class online and coming back from the five minute break, the teacher asked, Did everyone just check on the election? We were all waiting to hear if Jon Ossoff won the Senate race in Georgia. But the big Trump rally was also just starting in D.C., protesting against Congress accepting the Electoral College votes. I said, I was just checking to be sure the Trump people haven’t burned Washington to the ground.

Not meaning to be prescient.

And then feeling, very shortly, when they stormed the Capitol, that I had been.

Now, a day later, I feel glad I was not fully right, since the Capitol—with bullet holes and blood smeared statues—still stands.

Yesterday, when I walked out on the ice, I just walked along the shoreline. Walking from one lakeshore park, past all the houses, to another where I returned to snow-covered land. A man passed me on skis, his dog running along beside him. I have always loved the way that Madison, a town built on a narrow isthmus between two large lakes, gains this extra open space in winter, sudden frozen parks for dogs and people opening off the crowded, close neighborhoods of older houses.

But at least once a year, I walk out to the very center of the lake. There the connection with other humans fades. All around white: above white sky and blurred, faint white sun, below my feet a white dusting of snow over thick, hard ice, then deeper still cold, cold water. Standing there, it is hard to remember which way you came, which way is back to shore.

You step off the map and into the unknown.

Yesterday, with the Confederate flags flying in the U.S. Capitol, broken glass on the marble floors, was that mapless day politically. Republican politicians fled for their lives from the House and Senate chambers, then returned where far too many of them voted in support of the very thing the invaders wanted—the overturning of a presidential election. Elected representatives voting for the end of representative democracy.

It was a day that made me want to walk out into the middle of the lake where there were no humans. And stay there.

It has been a year (and a few days of another) where Covid made us all walk away from other humans — with good reason. And here was another plague on our houses.

So — where is the map that shows us the way — forward or at least back to solid land?

8.

I am thinking about a particular map.

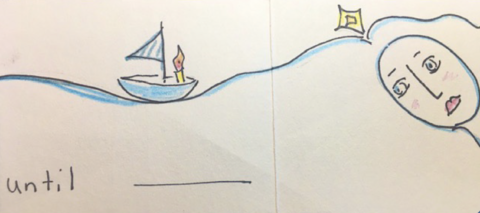

The only map I did draw was in an artist book I made for a class I took in December. It is a small book, only two inches square, a single page folded and cut to have a story that starts on the front and then continues on the back. The assignment was a treasure map, something that showed a friend, perhaps, the way to somewhere special.

I drew a journey, image by image, looking for the goddess Iemanjá, the mother of the sea. February 2 is the day her believers in Uruguay dedicate to her. She is the protector of

women, but her followers believe she cares deeply for all her children, comforting them and cleansing them of sorrow.

The book starts with two pages looking out at the city from my 7th floor apartment in Montevideo, just as I described earlier and follows part of the same journey. Each page or double spread of pages has an image and this text:

You can see a sliver of water through the window Take the elevator down

Cross Bulevar España

Pass the feria in Parque Rodó

Pass the Montaña Ruse in the Fun Park and the Ferris Wheel

Pass the ice cream cart And the torta frita stand

Until you are standing on the sand of Playa Ramírez

With nothing but water in front you stretching to Antartica

Buy a paper boat with a candle in it

Set it afloat with your prayers

On the sea with all the other little boats Sailing through the night

Until …

If I go out now and put a paper boat with a lit candle on lake, even though water is frozen, will it know — even without a map — where to go?

Jesse, I loved your essay, how you move between art and language as you search and create maps. Maps….”….ones that let imagination and image open a window to the world I know is still out there.”Keep writing and drawing and telling us more……Cheers, Pam