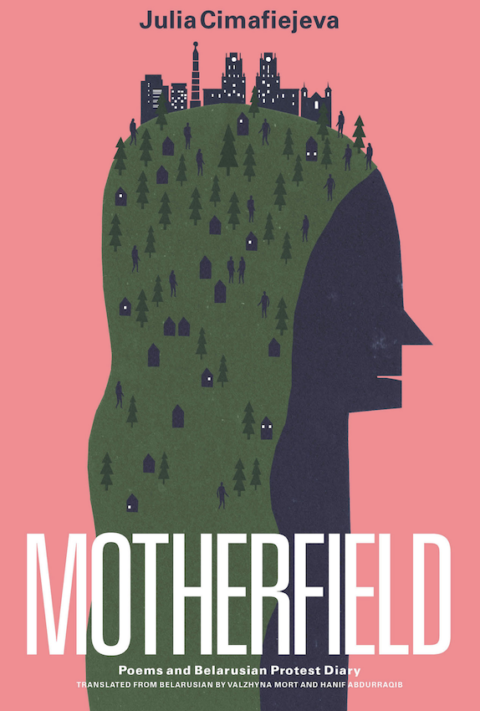

Julia Cimafiejeva’s Motherfield charts the poet’s insistence on self-determination in authoritarian, patriarchal Belarus, and paints an intimate portrait of fear, despair, hope, and guilt during a time of political unrest and police terror. A poet’s chronicle of protest, these poems also pose profound questions of identity, belonging, and inheritance.

Julia Cimafiejeva’s Motherfield charts the poet’s insistence on self-determination in authoritarian, patriarchal Belarus, and paints an intimate portrait of fear, despair, hope, and guilt during a time of political unrest and police terror. A poet’s chronicle of protest, these poems also pose profound questions of identity, belonging, and inheritance.

/ / / / /

In the Garden of Great-Grandmothers

Grandnanas, great-grandmamas, great-great-grandparents,

itty-bitty, transparent, dressed

in earth fluff, puffing into their palms,

they perch on my ears and tweet:

Here’s your field.

Here’s your calendar.

Sow, girl!

I’m so for it. I farm.

But in my field grow only

red grass,

green grief

that reeks of guilt and shame, and gray verses.

Grandnanas, great-grandmamas, great-great-grandparents,

transparent and itty-bitty,

pure before the Lord,

they perch on my ears and tweet:

Here’s your field.

Here’s your calendar.

Work, girl.

Okay, I throw

seeds into the dry soil.

But in my field grow only

red grass,

green grief,

ill weeds,

mud words.

What to do with this field, grandmamas?

What to do, grandmamas, with this calendar?

* * * * *

1986

We couldn’t take you with us,

our legless houses.

We couldn’t carry you out on our shoulders,

our freshly ploughed fields.

Our graves,

we couldn’t dig out

the deep roots of your crosses

in order to transplant them

into new soil.

Apple gardens,

closed pink-white eyelids,

silent, hoping for our return.

When, impregnated with cesium,

your buds grew red,

starved feral cats

followed the stars back home,

but didn’t touch

your fruit.

Apples fell and rotted,

thirsty for our tears,

crosses dried up, gardens

got lost in the weeds

and grew silent.

Our houses aged,

losing their minds and memories.

Strangers tore out the floor,

took down from the walls our dusty carpets,

stole all of our sick belongings,

sick, uncurable belongings,

things silent about their sickness.

When after many years

we came back for a visit,

only cemetery crosses

waved at us with the rags

of their embroidered towels.

Neither houses

nor gardens,

nor apple trees

recognized us.

No matter how hard

our forgiving dead

begged them from their freshly

cleaned graves,

neither houses, nor gardens,

nor apple trees

forgave us.

* * * * *

Motherfield (1)

Motherfield, you are wide and lazy

like an old woman’s scarf.

you keep us bundled.

You keep us at hand,

short and hardworking,

you grip us by our muddy

rubber boots, by our deformed fingers,

by the necks darkened in the sun.

Motherfield has twisted us, forced us into

prostration. Our hands

are our only thoughts.

I’m a child of my motherland.

Motherfield owns me.

But my legs are limp,

my hands refuse to smooth out furrows.

I dig a tunnel, I run

from my native soil

into the underbelly

of the field.

Where does this heavy womb

lead? Where do these fertilized thighs

open? At the sea, the stars, the hills?

Is it safe to poke out?

Motherfield

has punished me for the escape —

it has transformed me

into a blind mole.

* * * * *

Motherfield (2)

Every year the motherfield is a bride

under a thin muslin of snow,

under the strict supervision of tradition,

it is smoothed with rakes,

combed with ploughs,

inseminated.

The pasture grows thick. The pasture glows,

listening to the many-hearted beating

of potato plants.

Pasture cannot rise.

It lies spread out, finicky about weeds.

Asks for sunlight. Asks for water.

In the fall, laboring pasture quivers

from the first frost,

shudders in the last spasm,

and out spill into baskets

its round newborns.

An emptied pasture exhales

and closes its pebbly eyes.

Rest, old motherfield.

A new labor is ahead.

* * * * *

Negative Linguistic Capability

The language I can speak

is not my language.

The language I wish to speak

isn’t contained in words

I know,

isn’t contained in images

I see.

For my language there are no dictionaries,

no agreed upon rules.

It’s a language for reading my own self,

language for reading with mistakes,

because there is no one to correct me.

I will never write in this language.

If you are reading this poem,

you are not my reader.

/ / / / /

Motherfield, poems by Julia Cimafiejeva, is published by Deep Vellum Books. To obtain a copy from the publisher, click here.

Motherfield, poems by Julia Cimafiejeva, is published by Deep Vellum Books. To obtain a copy from the publisher, click here.