“Both Silence and Words”: Two Books, a Video, and a Surveillance File

“The one who merely flees is not yet free. In fleeing he is still conditioned by that from which he flees.”

― Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline & Critical Writings

1

A review is a formal assessment of an object with an eye to improving its style. A review is also a critical appraisal of a book, media, or art. The noun, review, usually designates the finished product.

I have written reviews before – it should not be difficult – particularly since the writer whose work I’m now focused on has themes which my own writing explored, and since the writer’s background is similar to mine, or the same limbo between lands and languages.

And to review her memoir alongside her book on poetics – to create a space for dialogue between those two genres, is a smooth pitch. It is not a complicated one. The template for such dialogues exists, the directionality is common. There’s nothing extraordinary in the effort I set for myself.

2

The review is made easier by the fact that the memoir won a prize. And the author, Carmen Bugan, is a woman, a mother, a daughter, a poet, a refugee, a part of the Romanian diaspora, an academic. Her memoir is spoken in first person, in a language devoid of sentimentality, remarkable for its flattened affect, its refusal to ply our pity or demand emotional investment. Her essays, also written in first person, reveal a mind which attempts to understand the past through literature and poetry. All the spaces touched by the essays and memoir are palpated by Bugan’s poems.

Since the essayist, poet, and memoirist revisit the same moments in time, they rub the stone of the same memories.

The text assumes we can meet the author in the space of articulated memory. The decision to read assumes that meaning can occur: it trusts that language may become the site of meaning. Taking each form as a lens, one can swivel between Bugan’s poems, memoirs, and essays with an eye on the same event.

“I will approach both books through the poetics of quotation,” I tell myself. This frame will allow me to discuss Carmen Bugan’s poetics alongside the role played by memory and surveillance files.

3

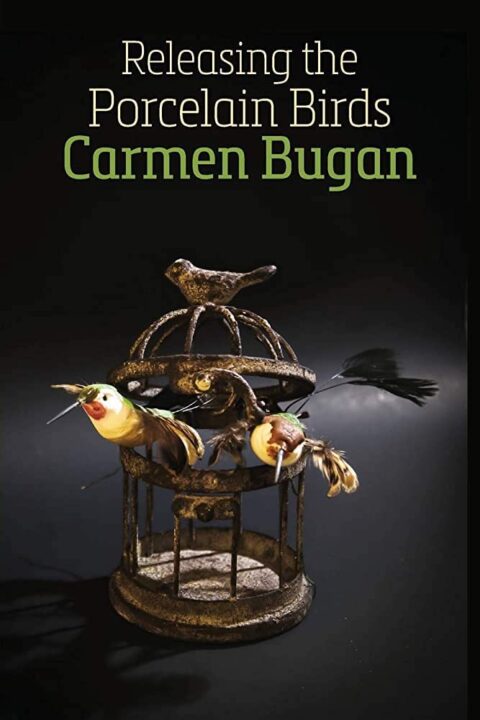

Dialoguing with other writers across texts, Bugan studies the silences where the writer’s responsibility to witness exists alongside the commitment to art by “taking denatured language and turning it into a language that cleanses the wounds.” Quotation is central to how Bugan brings the files to bear on the poems; what she calls “a poetics of quotation marks” tugs the language of oppression into the poem, using one language “in order to stare down the other,” as she describes in her book, Releasing the Porcelain Birds: Poems After Surveillance (Shearsman, 2016).

The writer is bracketed by quotations — by the identities ascribed to her based on ethnicity, national origin, and immigration—but she is also conversant with them. A “poetics of quotation marks” encompasses the experience of exile as well as the bilingual self in translation.

The writer is bracketed by quotations — by the identities ascribed to her based on ethnicity, national origin, and immigration—but she is also conversant with them. A “poetics of quotation marks” encompasses the experience of exile as well as the bilingual self in translation.

And quotation creates the impossible, which is to say, it makes the page a space for dialogue between texts and speech acts, between speeches and notebooks. By committing to this space, Bugan expands both time and place, enabling her to write into silences marked by the sins of the father, as the daughter of a political prisoner, or dissident.

“The persecution which my parents and we children endured as a result of my father’s protest forms the background to my poetry,” she explains. Bugan identifies as “an immigrant working at what might be called the confluence of languages,” in the spaces where languages meet in the mouth of a river.

Ultimately, however, Bugan’s academic essays, poems, and memoir offer a life built from poetry – not because poetry would make her a poet, but because poetry is the space in which the self could be rendered whole. This is my working thesis.

4

This is an essay about two books.

Inadvertently, it has also become a book-length manuscript about my failure to write an essay about these two books. It is a letter to those whom I have failed, and to those whom I will certainly fail when (or if) this book is published.

This is not a book I wanted to write. It is a vicious magnet that distracts me from the novel, the poetry, the manuscripts left in the lurch.

5

The Romanian regime drew its authority from documentary writing, which is to say: all writing became a form of documentary writing in that it reflected the new reality. All writing was therefore “realistic,” nothing was surreal, supernatural, supranatural, fantastic, or speculative. Each word was significant, and weighted by its relation to the regime’s project. Socialist (or Soviet) realism emphasized this aspect of realism.

From the beginning, it was known that history needed to be rewritten — that the single, absolute reading needed to exist in order for the church to determine which reading was heretical. The heretic loses access to God and community if he reads his life, his body, the text differently. The enemy — bourgeois individualistic romanticism — would be defeated by the plural voice of the worker hero. Unfortunately, heroism, itself, requires romanticizing an individual.

6

“In writing, I had both silence and words,” Bugan writes, revealing silence as a structural element of dictatorship, as in, for example, the power of the pause — the caesura – and how it creates a sticky space in which associations and lined works are allowed to connect and cohere.

The poet alludes to the “language of oppression.” When speaking to US-born friends, I realize that they interpret this language through the miasma of their own cultural myths and contexts. They are, after all, human.

An American academic who has published several studies of Eastern European culture tells me of Romania: “That’s just how things are over there.” She is a notable scholar, a generous human with an affinity for Eastern Europeans whose single connection to the Balkans comes from personal attraction. She has little to lose. Her life is not moored to the silences of Faustian bargain. As a result, she is considered an “objective source” on how things are over there.

7

Bugan wishes to maintain critical distance between the girl and the woman, but the persistence of themes challenges this effort. There are no clearer answers now. There is no epiphany. The dictator remains in the throats of Romanians like herpes, an infection buried so deep that one can barely speak of it. It cannot be unspoken or rinsed away. And no one will open their mouth wide enough in order to let you look inside their throat.

Bugan wishes to maintain critical distance between the girl and the woman, but the persistence of themes challenges this effort. There are no clearer answers now. There is no epiphany. The dictator remains in the throats of Romanians like herpes, an infection buried so deep that one can barely speak of it. It cannot be unspoken or rinsed away. And no one will open their mouth wide enough in order to let you look inside their throat.

The police file, the paranoia, the silences in my own family carve themselves into the margins of my reading like cenotaphs. I cannot find a way to name them or move them. Yet I must move them out of the way in order to write clearly, to maintain the sort of vigorous movement associated with critique.

Do silences want libation? Is there a first drop I owe the silence before being able to continue? Perhaps talking about silences will appease them, I think as I dial my father’s phone number for relief. He responds, and launches into a monologue about the turtle he found near the river which has become a dear pet, “Turdy …”

I cut him off — “Who wrote the revolution?”

8

In December 1989, Carmen and her family arrived in the United States as political refugees from Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorship. A few weeks later, they sat in front of a donated American television and watched “the Romanian revolution.” In these newsreels, the dictator looks down from a balcony at the staged demonstration of support. The image shifts — a few boos from the crowd alter the site of the spectacle — a flash of surprise crosses the dictator’s face. The controlled fiction of utopia is replaced by the controlled screening of an internal coup staged by Communist Party members. But for now, the usual scripts are upended. The camera keeps panning the author-less revolution.

Like many other Romanian refugees (including my parents), the Bugans oscillated between joy, fear, and disbelief in the months that followed. The impossible had happened. The unmovable had moved. When Ceausescu’s bullet-marked body was broadcast on international television, as if to provide concrete evidence of the dictatorship’s death, the Romanian diaspora cheered. And then they paused. And then they began whispering.

Like many other Romanian refugees (including my parents), the Bugans oscillated between joy, fear, and disbelief in the months that followed. The impossible had happened. The unmovable had moved. When Ceausescu’s bullet-marked body was broadcast on international television, as if to provide concrete evidence of the dictatorship’s death, the Romanian diaspora cheered. And then they paused. And then they began whispering.

No other Eastern bloc states displayed live executions of their leaders on television during the 1989 revolutions. Only the Romanian stage featured blood from the citizens in the square, blood în Timișoara, and blood from firing squad’s guns. By serving as the site of symbolic death, the dictator’s televised corpse made it possible for other Party apparatchiks to take power, recasting themselves as the Opposition, beating their chests with grief for the nation while platforming national unity. The official narrative existed in documentary form. The secret police surveillance files of dictatorships exemplify this epistemic and perspectival complexity.

Do we read the information in secret police files as fact, or as the speculative fictions of a police state? How does privacy inform our understanding of personhood? These questions haunted my recent reading of two books by Carmen Bugan, a writer whose life has been marked by borders demarcating the speakable from the unspeakable, the thought from the crime, the self from the state, the I from the We. All Bugan’s writing palpates these borders repetitively, carving a relationship with the literature of state surveillance.

9

What do I know about quotation?

This question is both rhetorical and critical. The paragraphs of the previous section 8 are quoted from my final draft of the review, captioned “Introduction,” dated to the year when I was trying to write it.

I’m sure you can see why I could not turn in this draft — or leave the gaping holes open for wind to whistle over them. I am quoting myself to make my failure legible.

10

“Historians and archaeologists are those who build on the presumed accuracy of archives and documents, but sometimes the veracity of these documents and archives causes history to be rewritten falsely. The surveillance files should be read in light of their role as a monument to the paranoid reading of dictatorship, pointing to the void at the heart of the dictator’s fiction. Given the fragmented, frantic shape of Securitate files, the only account one can give is that of an absence which the future will read into. This use of incompletion, this embrace of what cannot be entirely explained, enables us not only to speak with ghosts but also to be humble, to realize that we cannot override a past whose wounds are still open, and whose graves are still hidden.”

The preceding paragraph is quoted from the notes I took in early drafts, at a time when I believed Bugan’s books would make it possible to tell a linear story. Or when I believed that the critic could read from a position of neutrality. We see what we’ve been taught to value, and the American in me had little reason to disbelieve the value of seeing.

11

“Burying the Typewriter: Childhood Under the Eye of the Secret Police, winner of the 2012 Bakeless Prize from Graywolf Press, recounts the experience of Carmen Bugan’s life as a child and young adult in Ceausescu’s Romania as the daughter of a political dissident. More recently, Poetry and the Language of Oppression: Essays on Politics and Poetics (Oxford University Press, 2021) continues this journey through the mind of this daughter as she explores the language of poetry. The five essays touch on poetic lineage – the writers who instructed her as both a reader and a poet and how words change across the borders of language, culture, time, and politics. Like many poets in exile, Bugan believes poetry’s power comes less from deposing dictators than from opening speech to probe the inarticulable. Because the languages of poetry and suffering are often co-present, they collude in vulnerability, revealing the human condition. Her poetics testifies to a hope against hope, a resistance which isn’t rooted in outcomes. In this relinquishing of achievement or metrics for success, Bugan’s mode is loosely existentialist, or driven by the duty of speaking truth for its own sake.

“Both books probe similar themes — the surveillance files, the role of language, poetry’s relationship to power or propaganda. In the essays, Bugan’s voice is gently persuasive, trepidatious; she qualifies her statements repeatedly while pacing back and forth between ideas, poems, and writers who influenced her. The effect is dreamy, discursive, and intertextual — one hears a female academic trying to find acceptance or establish a place of belonging without upsetting the dominant powers.

“In contrast, the memoir is narrated in a flattened affect, tuned neutral, the timbre guise thoughts from others. Rather than interpreting events, Bugan describes life as it occurred between arrests and school. This defamiliarized banality feels more traumatized, more at-risk, than a voice who could engage the pain emotionally. Strong emotional valence is reserved for the three areas in which a counter-discourse challenges the official one, namely, her grandparents’ village life, poetry, and the physical reality of the secret police files. “

The two preceding paragraphs offer an alternate version of the introduction to the review; this one taken from The First Draft, the draft titled: “Lyric, Silence, and the Literature of State Surveillance in Carmen Bugan: An inventory.” I’ll be damned if I am not quoting my drafts. Again.

12

What is it like to find records of public documents organized as a sort of montage, including intimate private details of one’s life, organized as a story to be constructed, reread, analyzed, and interpreted?

Is there something “American” in Bugan‘s story? Not that I can find. The scholar trying to survive displacement adopts the language of the powerful. She resists it in poetry. She struggles alone in a room at night, torn between the marketable immigrant story and the complexity of defecting.

Is there something “American” in Bugan‘s story? Not that I can find. The scholar trying to survive displacement adopts the language of the powerful. She resists it in poetry. She struggles alone in a room at night, torn between the marketable immigrant story and the complexity of defecting.

“Look!” I tell my children at the soccer game, pointing towards the hot goalie. “The self is a speculative fiction!”

To read one’s self as a speculative fiction spans the unspeakability of trauma as well as a horrifying fascination of the eerie. Ontological displacement renders the text itself a form of art, or an authority.

Scholar Christina Vatulescu studied under Svetlana Boym. She is an archivist, a stacks-lover, a preserver of small details whose reading of surveillance files renders archives and documentary reports untrustworthy. She is brilliant. I am consumed by the stories I am not telling.

13

I return to Bugan’s caesura. Caesura comes from the tyrant, from tyranny’s warping of language. Caesar’s pauses spoke through implication — the pauses signaled new purges, new key words, shifting ideological winds. The dictator’s pauses were ominous, dangerous, and indecipherable.

Traditionally, in poetry, the caesura is a break in a metrical line which comes after the 2nd or 3rd beat. In modern verse, a caesura is a pause near the middle of a line, an interruption, a break inside a line.

The power of the caesura comes from its stickiness, the way which associations and linked words are allowed to connect and cohere. Music is central to my understanding of the caesura, which, for me, feels connected to the cadence. In an essay or musical composition, the interlude enacts a sort of intentional silence which enables cohesion. We notice it as a pause, or a shift in direction, but it is also a moment of silence that allows us to hear the symphony of aluminum cans attached to the rear bumper of a car that just flew past.

An imperfect (or half) cadence is a pause. In poetry and prose, the half cadence is represented with a comma, or a semicolon. The half-cadence’s rhythm refuses to sound final; it causes the line to end in the tension generated by indecisiveness.

A perfect (or authentic) cadence comes at the end of a phrase in a poem. How can I describe the cadences lodged in the throat of those who fled?

14

Obviously, this is a book about poetry — more specifically, about language and what lies beneath it. It circles the poet’s inability to find a boundary which matches the maps constructed by others. The poet’s mind is the divided land — the right leg alienated from the left, the common body that doesn’t match the borders of nation-states.

Admittedly, the book begins, and ends, with indescribable love for Carmen Bugan, the person, the daughter of a dissident, the child, the mother, the writer.

Mark Fisher defines “ontological hesitation” as “that moment when one is asked to decide if this is real or not real.” If it’s not real, is it at least some aesthetic transposition of the real, as in a Gothic colonnade or a cocktail party? Time travel conceits often rely on this ontological hesitation to build dynamic tension into the work. Tristan Todorov delineated “the fantastic” as that which waivers between the uncanny, which can only be explained naturalistically, and the marvelous, which can only be explained supernaturally. The self shudders before its selfhood.

Mark Fisher defines “ontological hesitation” as “that moment when one is asked to decide if this is real or not real.” If it’s not real, is it at least some aesthetic transposition of the real, as in a Gothic colonnade or a cocktail party? Time travel conceits often rely on this ontological hesitation to build dynamic tension into the work. Tristan Todorov delineated “the fantastic” as that which waivers between the uncanny, which can only be explained naturalistically, and the marvelous, which can only be explained supernaturally. The self shudders before its selfhood.

You, reader, are at the beginning. Everything that will happen is ahead. There are photos of Bugan’s family, excerpts from surveillance files, stills from documentary movies under Ceausescu, poems about village traditions in which Bugan recreates the single space of safety during her childhood, ghosted conversations between other Romanians who left, including Emil Cioran and Benjamin Fondane. Everyone in this book is a criminal. Every character participates in sustaining various carceral modes.

Something stirs beneath these stills, these photos, these words – something that was frozen in motion—and it is the motion hailed by the image which haunts me most. It is the lie of finishedness in the image. It is the lie of documentary art’s capacity to bear witness.