on Wings of Red, a novel by James W. Jennings

“My being homeless is merely comedy until it dawns on me, listening to my own footsteps, that I’ve fallen for the pretty girl who can have whoever she wants. It’s a strange thing not to realize until now.” The pretty girl is New City, aka New York. The narrator has just come to the end of his apartment lease and still owes rent for the previous month – he’s newly homeless. Here is his more formal introduction:

“I have a master’s degree in fine arts. I also have $100K in student loans and transgressions on my record that at times require explanation. As far as society’s concerned, it’s these two odd extremes that define me. There’s no real context or content, but often these are the two notes that get bureaucratic gears to moving. There I am. June Papers. Twenty-eight years old. MFA with a felony. The classic young, Black, and gifted American misfit.” He is also the author of a self-published novel, Strays or United Strays of America, “a cold press of my reckless sophomore year in college.”

“I have a master’s degree in fine arts. I also have $100K in student loans and transgressions on my record that at times require explanation. As far as society’s concerned, it’s these two odd extremes that define me. There’s no real context or content, but often these are the two notes that get bureaucratic gears to moving. There I am. June Papers. Twenty-eight years old. MFA with a felony. The classic young, Black, and gifted American misfit.” He is also the author of a self-published novel, Strays or United Strays of America, “a cold press of my reckless sophomore year in college.”

Having entered James W. Jennings’ autofictional novel, Wings of Red, one walks or rides along beside June Papers from place to place – in subways and a friend’s car, having a meal here and there, finding a place to sleep or wash up, traveling briefly to see his grandmother, and at the school where he works as a substitute gym teacher. He describes himself as a “scribe,” the one among us who takes note and records his reactions in journals as testimony:

“I decide to journal daily now so that at the very least I’ll be able to see whether my issue is as simple as me. As for the fiction this is it. Doesn’t really matter what you call it once you live it. Against all good advice, my life and my literature are inseparable. I may be ashamed of my current predicament and embarrassed by the truth, but I’m 100 percent me, no matter what industry calls it. After a word or two it’s all fiction anyway.”

June may be accumulating papers with experiential materials for his next novel, but he already understands that the artifice of autofiction works to create the illusion that there is no artifice. It’s the artful illusion of truthfulness, rigged up from that oldest of tricks, the mixing of the recalled and the invented. “There was a major turning point in the editing of Strays where I realized I had to get rid of most of the political ideas and social commentary,” he recalls. “It killed the momentum of the story.” In an interview published in Shondaland, Jennings remarked, “For me as a creative, and just as a human being, to be honest, it’s always been about proximity to truth. Like, how close to your truth can you get? … So, I decided early I’m not going to do the hero’s journey. I’m not going to give Hollywood their script … Not stereotypes, not trying to fulfill your diversity, equity, and inclusion quota – actual Black narrative.”

What matters in Jennings’ novel is presence, made intriguing through an unerring ear for urgent statement, pacing of action (continuous, since June is on the move), and rhythm of expression. I came to regard Wings of Red as a picaresque novel, essentially comic in spirit. A “picaro” is a rogue and adventurer – and so is June Papers. When he commits a theft (“I decide to steal something as a middle finger to the invisible hands keeping good people down”), I’m cheering him on primarily because his tone is waggish and entertaining. It was Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the archetypal picaro, who brought the major comic tropes to the relation between fiction and reality. Don Quixote bristles with irreverence. When June says, “I wonder how it is I’m not a millionaire yet,” I recall Sancho Panza describing a “knight adventurer” like Don Quixote as “someone who’s beaten and then finds himself emperor.”

What matters in Jennings’ novel is presence, made intriguing through an unerring ear for urgent statement, pacing of action (continuous, since June is on the move), and rhythm of expression. I came to regard Wings of Red as a picaresque novel, essentially comic in spirit. A “picaro” is a rogue and adventurer – and so is June Papers. When he commits a theft (“I decide to steal something as a middle finger to the invisible hands keeping good people down”), I’m cheering him on primarily because his tone is waggish and entertaining. It was Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the archetypal picaro, who brought the major comic tropes to the relation between fiction and reality. Don Quixote bristles with irreverence. When June says, “I wonder how it is I’m not a millionaire yet,” I recall Sancho Panza describing a “knight adventurer” like Don Quixote as “someone who’s beaten and then finds himself emperor.”

June Papers is the emperor of his own sanguine spirit. The cogent liveliness of his narrative allows him to offer asides like, “All that really lasts is the living and whether you opened yourself up to the heartfelt possibility of your unique experience,“ repeated some pages later as, “All that really matters is the living – that you opened yourself up to the full responsibility of experience.” This may be an unnecessary reiteration – but Jennings gets away with this preachiness because it sounds natural to – and necessary for — June Papers. He dishes out such sagacity to the kids at school, though without expecting any of it to sink in. Jennings limns the school scenes with a fidelity to the actual.

Cervantes looked around post-medieval Europe and wondered: what are people? He considered courage, love, loyalty, winning and losing, exultation and humiliation – and then packed these attributes into his main character. James Jennings does the same thing with June Papers – minus shame and mortification, not that such emotions would be unjustified, but perhaps it is because their causes are so insidiously embedded in his world that being “100 percent me” must act as a sufficiently potent strategy to proceed through New City.

[Published by Soft Skull Press on November 21, 2023, 216 pages, $16.95 US paperback]

/ / /

on February 1933: The Winter of Literature by Uwe Wittstock, translated from the German by Daniel Bowles

On Tuesday, February 28, 1933, the new Chancellor of Germany, Adolph Hitler, placed two emergency decrees before Paul Hindenberg, President of the Weimar Republic. More concerned by the Communists than the Nazis, Hindenberg signed the documents, thus abolishing the constitutional state. The first order, the “Decree of the Reich President for the Defense of People and State,” canceled a citizen’s fundamental rights. Also on this day, Carl von Ossietsky, editor-in-chief of Die Weltbühne, was arrested and sent to Spandau prison with others. (Ossietsky will be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1936 while incarcerated at the Esterwegen concentration camp.) At the same time, Alfred Döblin, regarded by the new regime as “a liberal reactionary writer,” received phone calls from friends pleading with him to flee; he lingered in his apartment all day, then packed a small suitcase and walked to the subway station, followed by “a man wearing a civilian coat over his SA uniform” who boarded the train with him. Döblin eluded him and later caught the 10:00 pm train to Stuttgart; he then made his way to France and in 1940 headed to Los Angeles. Will he ever see Berlin again?

In February 1933: The Winter of Literature, journalist, critic and author Uwe Wittstock (b. 1955) takes the reader day by day, from January 28 to March 15, 1933, to animate darkly the concurrent acts of Germany’s most prominent writers and journalists, and their NSDAP antagonists. Employing the present tense and a terse mode of address, Wittstock generates the sinister aura that startled, confused, frightened, outraged, immobilized or provoked a range of cultural figures – including Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Käthe Kollwitz, Gottfried Benn, Georg Grosz, Elsa Lasker-Schüler, Bertolt Brecht, Hans Fallada and many others. Wittstock’s first sentences read:

In February 1933: The Winter of Literature, journalist, critic and author Uwe Wittstock (b. 1955) takes the reader day by day, from January 28 to March 15, 1933, to animate darkly the concurrent acts of Germany’s most prominent writers and journalists, and their NSDAP antagonists. Employing the present tense and a terse mode of address, Wittstock generates the sinister aura that startled, confused, frightened, outraged, immobilized or provoked a range of cultural figures – including Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Käthe Kollwitz, Gottfried Benn, Georg Grosz, Elsa Lasker-Schüler, Bertolt Brecht, Hans Fallada and many others. Wittstock’s first sentences read:

“These are no tales of heroes. They are stories of people facing extreme peril. Many of them refused to acknowledge the danger, underestimated it, reacted too slowly in short: they made mistakes. Of course, it is easy for anyone paging through history books today to say such people were fools if they could not comprehend in 1933 what Hitler meant for them. And yet such a notion would be unhistorical. If the claim that Hitler’s crimes are unimaginable has any meaning, then it must hold true first and foremost for his contemporaries.”

On Wednesday, February 15, Hitler’s minister without portfolio, Hermann Goring, denied a report by the British Times that the Prussian Interior Ministry intended to arm the right-wing political groups SA, SS, and the Stahlhelm veterans organization and deploy them as auxiliary police forces; there were 500,000 men in their ranks. But skirmishes, some lethal, had been going on for months before Hitler’s ascendancy as these cadres fought in the streets against groups of socialists and communists. The disorder that Hitler’s new degrees targeted was triggered by the SA and SS themselves; the populace called for an end to the violence and was happy to see the Nazis enforce it.

In contrast to Hitler’s determination to scrap German democracy, the country’s literary luminaries argued over how to proceed. At the Prussian Academy of the Arts, where the country’s great artists and writers convened, contention erupted: Kollwitz and Heinrich Mann had signed an “Urgent Call for Unity,” demanding the closing of ranks between the two socialist parties, the SPD and KPD. Prussia’s education minister, Bernhard Rust, wanted them expelled from the Academy. Benn and Döblin argued. Wittstock’s incisive portraits not only animate these characters, but ultimately emphasize the irrelevance of literary considerations in the face of overwhelming violence and wrested control.

Upon the burning of the Reichstag on February 27, Hitler’s decrees were announced; a month later, parliament was dissolved. In the meantime, the SA and SS showed up at theaters and shut down offending performances. Chiefs of police were fired and replaced with Hitler’s people. The first major book burning took place on March 7. And of course, Jews in all professions were dismissed, starting with the writers, playwrights and journalists. Wittstock follows these characters as they meet at their favorite cafes for the final times, make plans to depart before their travel visas expire, sell off their furniture and jewelry, and withdraw whatever funds they can, if any, from their bank accounts.

Upon the burning of the Reichstag on February 27, Hitler’s decrees were announced; a month later, parliament was dissolved. In the meantime, the SA and SS showed up at theaters and shut down offending performances. Chiefs of police were fired and replaced with Hitler’s people. The first major book burning took place on March 7. And of course, Jews in all professions were dismissed, starting with the writers, playwrights and journalists. Wittstock follows these characters as they meet at their favorite cafes for the final times, make plans to depart before their travel visas expire, sell off their furniture and jewelry, and withdraw whatever funds they can, if any, from their bank accounts.

Most poignant is Bertold Brecht’s situation. He and his wife held travel vias, but not their two-year old daughter Barbara. Two of his new plays had just been cancelled. The Brechts went to Prague, then Vienna, Zurich and Paris. It was Brecht, in his 1935 essay “Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties,” who stated, “Many of the persecuted lose their capacity for seeing their own mistakes … The persecutors are wicked simply because they persecute; the persecuted suffer because of their goodness. But this goodness has been beaten, defeated, suppressed, it was therefore a weak goodness, a bad, indefensible, unreliable goodness … It takes courage to say that the good were defeated not because they were good, but because they were weak” (italics Brecht’s).

Wittstock’s spine-stiffening narrative, increasingly grim as the days of February 1933 pass, provides the context for assessing our own goodness and weakness.

[Published by Polity on July 3, 2023, 275 pages, $29.95 US hardcover. First published in 2018 by Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Munich]

/ / /

Published in Japan in 1951, Yasunari Kawabata’s novel The Rainbow pivots between two sisters: Momoko, mourning the death of her lover, a pilot, during the war, now runs headlong into unsatisfying and even cruel relationships – and her younger, sensitive sister, Asako, who is preoccupied with finding their estranged sister. As in his pre-war novels, Kawabata treats these intimacies with restraint, such that when an admission or accusation is voiced, it delivers great force within the quietude. Taking place during 1950, just five years after two atom bombs, Kawabata’s novel seems to be asking implicitly: What is Japan now? What are we now that our exertions have resulted in such defeat? Are our traditional values still relevant?

Published in Japan in 1951, Yasunari Kawabata’s novel The Rainbow pivots between two sisters: Momoko, mourning the death of her lover, a pilot, during the war, now runs headlong into unsatisfying and even cruel relationships – and her younger, sensitive sister, Asako, who is preoccupied with finding their estranged sister. As in his pre-war novels, Kawabata treats these intimacies with restraint, such that when an admission or accusation is voiced, it delivers great force within the quietude. Taking place during 1950, just five years after two atom bombs, Kawabata’s novel seems to be asking implicitly: What is Japan now? What are we now that our exertions have resulted in such defeat? Are our traditional values still relevant?

Perhaps the pivot-point itself is the sisters’ father, Mizuhara Tsuneo, an accomplished architect whose three daughters were conceived with three different women. The mothers of Asako and Momoko are dead. Did one of them commit suicide? A fog of secrecy hovers over the family amid the almost-dissipated smoke of war. Mizuhara visits the sites of classical beauty, such as the Daitokuji temple in Kyoto, where the preceptor’s wife remarks, “These après-guerre children are like raging bulls, always breaking this and that” – after complaining that “children were all but destroying the temple grounds. The damage caused when they played baseball was apparently the most serious by far.” Later, a client named Aoki, whose residence Mizuhara designed and now returns to, says, “I spoke to the head of the Urasenke school of the tea ceremony. He said most men who come to him wear Western clothes these days Before the war … it would have been considered unbecoming, a breach of basic etiquette.” And then, “There were no atomic bombs in Rikyu’s day. Maybe I should have asked you to build me a bomb shelter before worrying about a tearoom.” In The Rainbow, most of what we learn comes from overhearing conversations.

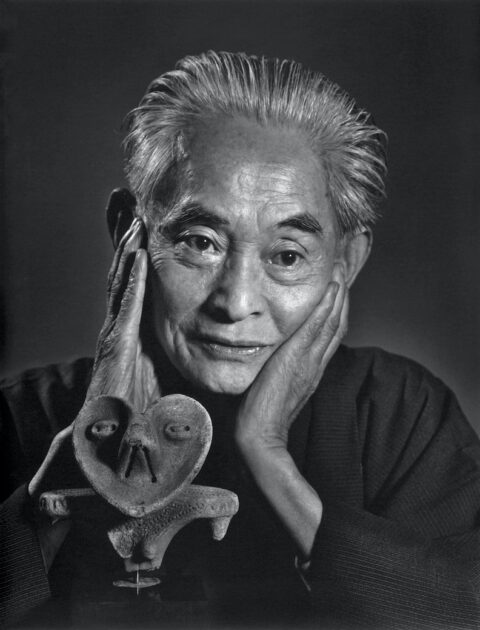

As tension rises between the two sisters, Mizuhara, the architect of the familial situation, seems strangely impotent. “The ways in which children born to the same mothers tended to resemble their parents, while at the same time differing from them, was indeed curious,” to Mizuhara, “but in his case, the fact that his three daughters each resembled their different mothers so remarkably, and at the same time resembled him, seemed to Mizuhara stranger still.” But one wonders why this seems so odd to him. He neither explains much about the past, nor does he speak of a way forward in his work. Yet he remains at the center of the action. The disarray in his family is the disarray of Japan; can there be a viable future if the reasons for such turmoil are ungraspable? The historic royal residences are being subdivided into living spaces for those who lost their homes. Meanwhile, Momoko loses a boyfriend to suicide and receives unexpected news about her health, while Asako obsesses over the third sister, now a geisha. Although Kawabata doesn’t allow analysis or sentimentality, he does permit Aoki, who is also the father of Momoko’s dead kamikaze pilot, to say, “trying to separate our individual fate from the people and the world around us leads only to loneliness and solitude.” Kawabata wants us to assess just how separated the father and sisters have become. He knew something about separation, having been raised by his paternal grandparents, orphaned at age 4. By age 15, there were no close family members left for him to turn to.

As tension rises between the two sisters, Mizuhara, the architect of the familial situation, seems strangely impotent. “The ways in which children born to the same mothers tended to resemble their parents, while at the same time differing from them, was indeed curious,” to Mizuhara, “but in his case, the fact that his three daughters each resembled their different mothers so remarkably, and at the same time resembled him, seemed to Mizuhara stranger still.” But one wonders why this seems so odd to him. He neither explains much about the past, nor does he speak of a way forward in his work. Yet he remains at the center of the action. The disarray in his family is the disarray of Japan; can there be a viable future if the reasons for such turmoil are ungraspable? The historic royal residences are being subdivided into living spaces for those who lost their homes. Meanwhile, Momoko loses a boyfriend to suicide and receives unexpected news about her health, while Asako obsesses over the third sister, now a geisha. Although Kawabata doesn’t allow analysis or sentimentality, he does permit Aoki, who is also the father of Momoko’s dead kamikaze pilot, to say, “trying to separate our individual fate from the people and the world around us leads only to loneliness and solitude.” Kawabata wants us to assess just how separated the father and sisters have become. He knew something about separation, having been raised by his paternal grandparents, orphaned at age 4. By age 15, there were no close family members left for him to turn to.

The Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Kawabata in 1968. He died in 1972, apparently via suicide by gas. In America, where the superb novels Snow Country and Thousand Cranes (both translated by Edward Seidensticker) appeared in 1956 and 1958 respectively, readers became acquainted with Kawabata’s pre-war work. But with The Rainbow, we can now hear certain melancholic tones, and Kawabata’s exquisite phrasing allows us to hear what the psyche sounds like after tumult and horror. Here I give thanks to Haydn Trowell for the refinement of this rendition; I think of the challenge Kawabata presents to the translator – the exquisite work of untranslatability. And of course, there is the rainbow, glimpsed in the first chapter and shimmering later in the story – the actuality of ungraspable beauty.

[Published by Vintage Books on November 7, 2023, 251 pages, $23.00 US paperback]