Literary critics usually place Jean-Luc Benoziglio’s novels within the late century post-structuralist mode. His texts, they say, are presences in themselves, not intended to direct the reader’s gaze to a world beyond words. His parodic manner disparages literary conventions. And so on.

But Benoziglio was disinterested in language theory and had almost nothing to say about his intentions, influences, and values. He was part of no clique though he followed the works of some Oulipians. He may be one the most striking examples of a postmodern writer whose style emerged ex nihilo from personal ferment, quirky determination, and hypersensitivity to the encroaching surround of western European political and cultural turbulence. Writing obsessively and continuously as a practice, he produced 15 novels in 35 years. Editions du Seuil loyally published them all.

But Benoziglio was disinterested in language theory and had almost nothing to say about his intentions, influences, and values. He was part of no clique though he followed the works of some Oulipians. He may be one the most striking examples of a postmodern writer whose style emerged ex nihilo from personal ferment, quirky determination, and hypersensitivity to the encroaching surround of western European political and cultural turbulence. Writing obsessively and continuously as a practice, he produced 15 novels in 35 years. Editions du Seuil loyally published them all.

Born in Switzerland in 1941, Benoziglio moved to Paris in 1967 after dropping out of law school. His first novel was published in 1972. Eight years later, he won the Prix Médicis for Cabinet-portrait, his sixth. (The 1980 Médicis was first awarded to – and refused by — Jean Lahougue.) Through a lively translation by Tess Lewis, Privy Portrait is now the first of his novels available in English. But even in Europe, his novels are not widely available – only five have been published in German versions.

Privy Portrait is a darkly comic story narrated by an unnamed man at mid-life whose wife Stérile and daughter Stéphanie have left him. (Yes, Stérile.) No longer stably employed, he has taken jobs as a security guard though he is nearly incapable of protecting his own interests (“To think that two or three of my Jewish ancestors were liquidated on the pretext that their business gene was overdeveloped.”) He is blind in one eye and experiences sharp gut-pains that he fears are cancerous. In the opening scenes, he describes packing up his belongings and moving to a smaller apartment in Paris with the help of two hired hands (he names them Asparagus and Brick House). The reader soon understands how Benoziglio wants us to proceed – haltingly with little traction.

Privy Portrait is a darkly comic story narrated by an unnamed man at mid-life whose wife Stérile and daughter Stéphanie have left him. (Yes, Stérile.) No longer stably employed, he has taken jobs as a security guard though he is nearly incapable of protecting his own interests (“To think that two or three of my Jewish ancestors were liquidated on the pretext that their business gene was overdeveloped.”) He is blind in one eye and experiences sharp gut-pains that he fears are cancerous. In the opening scenes, he describes packing up his belongings and moving to a smaller apartment in Paris with the help of two hired hands (he names them Asparagus and Brick House). The reader soon understands how Benoziglio wants us to proceed – haltingly with little traction.

There is no room for his massive set of encyclopedias so he installs them in the privy down the hall. He sits there for long periods, annoying the other residents, especially his arch-enemies, the anti-Semitic Sbritskys, man and wife. Flipping through the huge tomes, he makes a ragged attempt to discover his family’s origins. His paternal family was Spanish Jews who emigrated to Turkey and then to Switzerland (like Benoziglio’s). Through the thin wall of his unit, he can hear the Sbritsky’s TV broadcasting dire news about Anatolia where his sole known relative, a cousin, is living.

These are the bare facts of Privy Portrait — but it is dialogue, daydream, recalled events, and caustic self-assessment that fuel the prose. Entries from the encyclopedia are inserted in places. The narrator’s tone is bleakly emphatic, energetically critical. He irritates others but his judgments are often perceptive. His repetitive habits of speech may also annoy the reader – but he recoups with anecdote and small actions, and his terseness is often droll. Below, he remarks on his wedding:

“Our harmony lasted long enough for Sterile and me to hear the ‘yes’ said without conviction that everyone pronounces before an indifferent functionary who, we learn later, is in a hurry to finalize his own divorce in a neighboring office.”

The dead weight of the encyclopedias and the reek of the privy form the core of this story-existence. When the man meets his cousin in Paris, they seem capable only of clichéd conversation. Dialogue with the Sbritsky’s devolves into violence. But it is hard to concur with critics who believe Benoziglio “depreciates” language on principle. On the contrary, he has empowered it to communicate the brooding sense of futility in the mind of his narrator. The farce and frightfulness have entirely seeped into his interior – yet he is capable of mocking himself.

The dead weight of the encyclopedias and the reek of the privy form the core of this story-existence. When the man meets his cousin in Paris, they seem capable only of clichéd conversation. Dialogue with the Sbritsky’s devolves into violence. But it is hard to concur with critics who believe Benoziglio “depreciates” language on principle. On the contrary, he has empowered it to communicate the brooding sense of futility in the mind of his narrator. The farce and frightfulness have entirely seeped into his interior – yet he is capable of mocking himself.

It is also clear that Benoziglio intends language to convey very particular views about our world. Here, the speaker describes what he hears through the walls as the TV drones on:

“I soon ascertained, alas, that the almost uninterrupted noise of my neighbor’s television — not to mention the other nut job’s moaning — made concentrating on anything nearly impossible. Nothing is harder than trying to understand what separates two ethnic groups than a journalists’s booming voice describing live — he has no choice but to yell so he can be heard over the sounds of gunfire — the battles the two groups are waging against each other. At first, I dug my heels in and put my hands over my ears. I knew that my encyclopedia was my Bible and would help me understand the ins and outs of such confrontations. I knew things were never as simple as they wanted us to believe. They slaughtered each other and I retraced the centuries …”

Benoziglio’s final novel, Louis Capet (2005), fancifully imagines the exile of King Louis XVI to Switzerland in 1793. Obese and rheumatic, the banished ruler faces a tedious end. He is forced to sell his watch and eat a horrid cheese fondue. In the end, he is found in his little house with a broken neck – an accident – and is buried in the cemetery across the street. Benoziglio died in 2013 at age 72.

[Published by Seagull Books on September 8, 2014. 256 pages, $24.00 hardcover]

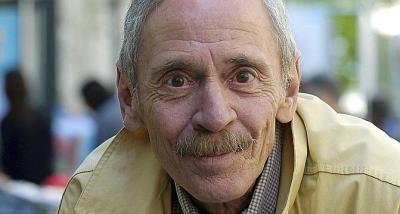

M. Benoziglio

Just read the final chapter of said novel. This machine runs on a propellant of sorts, pure narrative energy. It’s hard to sustain at a level that keeps one engaged. There are lags, there are sections of redundancy. But this is the fidelity to actual life, just the type of fiction we have no patience for on this shore. One hopes there will be more of Benoziglio for us en Anglais. The tale is notable for its expression of exile from all cultural and historical power and solidity, a man adrift on the edge, trying hard to keep his humor and vitality intact. Quite a project.

On The Separations of Understanding

Thank you for another fascinating review. I’m struck by the teller’s choice of the encyclopedia to gather knowledge of the world — by his evident solace in that — and his choice of privy (still the most dangerous room in the house) to suggest a certain irrelevance, where search is mediated by a private act. There’s the farcical ludus, maybe it’s just more knucklebones, but when understanding cannot be encoded except in a private setting (i.e. in a book), then words will always have the last laugh…because, sure, it’s impossible to know very much about anything.