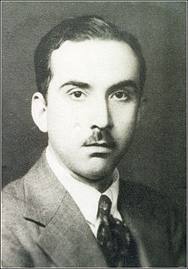

Martín Adán, the famously reclusive Peruvian poet and writer, was once approached by an Argentine doctoral student for an interview. He met with Celia Pachero but abruptly ended the dialogue after a few questions. Later he responded in his fashion by producing a poem addressed to her, “Written Blindly,” with these lines:

If you want to know about my life

go look at the Sea.

Why do you ask me, Learned One?

Don’t you know that in the World,

everything gathers from nothing,

from withering immensities,

nothing but an eternal trace

barely a shadow of desire?

Adán wrote but one novel, The Cardboard House (La casa de cartón), published in 1928 when he was just twenty years old. It is perhaps the most lyrically distinctive narrative of its time and place. Its premise: a man recalls his youth in the seaside resort of Barranco near Lima. His literary elders immediately recognized the work as exceptional and proclaimed it a masterpiece. Nevertheless, even today when presented to the American market (as in Publisher’s Weekly), The Cardboard House is described by what it’s not. (“If readers are willing to do without any thread connecting the fragments of this prose poem-novel …” etc., as if there are no connections!)

Adán wrote but one novel, The Cardboard House (La casa de cartón), published in 1928 when he was just twenty years old. It is perhaps the most lyrically distinctive narrative of its time and place. Its premise: a man recalls his youth in the seaside resort of Barranco near Lima. His literary elders immediately recognized the work as exceptional and proclaimed it a masterpiece. Nevertheless, even today when presented to the American market (as in Publisher’s Weekly), The Cardboard House is described by what it’s not. (“If readers are willing to do without any thread connecting the fragments of this prose poem-novel …” etc., as if there are no connections!)

In brief segments of a few pages, the speaker envisions a place:

“With their brooms, sharp and straight like paintbrushes, the street sweepers make drawings along the tree-lined streets. The street sweepers have the hair of aesthetes, the eyes of drug addicts, the silence of literary men. There are no penumbras. Yes, there is one penumbra: a burst of light in vain spreads through the street that grows longer and longer in order to cancel it out. Here a shadow is not the negation of the light. Here a shadow is ink: it covers things with an imperceptible dimension of thickness; it dyes. The light is a white floury dust that the wind disperses and carries far away.”

There is one accompanying character, a friend and rival named Ramón, repeatedly invoked like the god of vanished youth. Other friends are sketched, and there are several adolescent girlfriends. But at the core of the narrative is the speaking voice, reluctant to credit itself with defined edges. The modernist attitude toward the first-person flares with a rapacious ferocity for life, reaching toward reality by calling up juvenescence with the classic pleasures and terrors of archetype:

“My first love was twelve years old and had black fingernails. In that village of eleven thousand inhabitants and a publicity agent for a priest, my then Russian soul rescued the ugliest girl from her solitude with a grave, social, sober love like the closing session of an international workers’ congress. My love was vast, dark, sluggish, with a beard, glasses, and portfolios, with sudden incidents, twelve languages, police ambushes, problems from everywhere. She would say to me, when things became sexual, ‘You are a socialists.’ And her little soul – that of a pupil of European nuns – opened like a personal prayer book to the page about mortal sin.”

“My first love was twelve years old and had black fingernails. In that village of eleven thousand inhabitants and a publicity agent for a priest, my then Russian soul rescued the ugliest girl from her solitude with a grave, social, sober love like the closing session of an international workers’ congress. My love was vast, dark, sluggish, with a beard, glasses, and portfolios, with sudden incidents, twelve languages, police ambushes, problems from everywhere. She would say to me, when things became sexual, ‘You are a socialists.’ And her little soul – that of a pupil of European nuns – opened like a personal prayer book to the page about mortal sin.”

Strings of lush or stark description give way to angles on culture, the provisional but omnipresent nature of authority, the driven and aimless heart of human nature. But the cultural seeps back into the more dominant landscapes, the weather and the quality of light. This is memoir, but there is no implied mastery of the past, no primacy awarded to the facile. Yet every sentence hinges on an urgent clarity.

To explain the nature of his single “novel” and his poems, he told the grad student, “The real isn’t captured: it is followed.”

He wanted his sentences to be like the “hard and magnificent prose of city streets without aesthetic preoccupations.” Every so often, the first-person tentatively appears: “I am not wholly convinced of my own humanity; I do not wish to be like others. I do not want to be happy with the permission of the police.” He did not presume that the world’s lavish qualities existed for him to turn into sententious conclusions that reflect credit on the writer: “The world is insufficient for me. It is too large, and I cannot shred it into little satisfactions as I would like.” And a previously omitted fragment: “What were our ideas? The truth was, we didn’t have any. We believed vaguely in very vague vaguenesses.”

He wanted his sentences to be like the “hard and magnificent prose of city streets without aesthetic preoccupations.” Every so often, the first-person tentatively appears: “I am not wholly convinced of my own humanity; I do not wish to be like others. I do not want to be happy with the permission of the police.” He did not presume that the world’s lavish qualities existed for him to turn into sententious conclusions that reflect credit on the writer: “The world is insufficient for me. It is too large, and I cannot shred it into little satisfactions as I would like.” And a previously omitted fragment: “What were our ideas? The truth was, we didn’t have any. We believed vaguely in very vague vaguenesses.”

Graywolf Press published Katherine Silver’s original translation of The Cardboard House in 1990. The reissued version from New Directions includes “significant though not extensive changes” along with the poem “Written Blindly.”

“The city licks the night like a famished cat,” he wrote. The hunger for the real in The Cardboard House is exuberant, the self-view often mordant: “A crippled little dog walks by: the only compassion, the only charity, the only love of which I am capable.”

* * * * * * * * * *

Perhaps it’s no surprise that Martín Adán isn’t mentioned in Why This World, Benjamin Moser’s recent biography of Clarice Lispector. Although she read the Brazilian classics like Machado de Assis, her earliest interests were Euro-centric: Dostoevsky, Hesse and Flaubert. There are only occasional mentions of her exposure to and interaction with Hispanic writers. But for me, Adán and Lispector are closely related.

In 1920, Clarice was born Chaya Pinkhasovna in a Ukraine shtetl and came to Brazil the following year when her family fled the pogroms. Like Adán and other radically different prose writers of the early 20th century (affected by global war, displacement and exile, the loss of faith in institutions, the ebbing of colonialism, etc.), she accessed the freedom to find her style intuitively. Moser reminds us that “Hélène Cixous declared that Clarice Lispector was what Kafka would have been had he been a woman, or ‘if Rilke had been a Jewish Brazilian born in the Ukraine. If Rimbaud has been a mother … if Heidegger could have ceased being German.’ ” In her twenties, now the wife of a Brazilian diplomat and writing her first stories and novella, she was reading Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and the philosophy of Spinoza.

In 1920, Clarice was born Chaya Pinkhasovna in a Ukraine shtetl and came to Brazil the following year when her family fled the pogroms. Like Adán and other radically different prose writers of the early 20th century (affected by global war, displacement and exile, the loss of faith in institutions, the ebbing of colonialism, etc.), she accessed the freedom to find her style intuitively. Moser reminds us that “Hélène Cixous declared that Clarice Lispector was what Kafka would have been had he been a woman, or ‘if Rilke had been a Jewish Brazilian born in the Ukraine. If Rimbaud has been a mother … if Heidegger could have ceased being German.’ ” In her twenties, now the wife of a Brazilian diplomat and writing her first stories and novella, she was reading Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and the philosophy of Spinoza.

Published in 1973, Água Viva is the seventh of her nine novels. It purports to be the testimony of a painter who is now trying to do with words what she also attempts in paint. She addresses an unnamed, loved and forsaken other. If The Cardboard House chases reality by exchanging the integrity of the first-person for the speculations of a rich, non-linear memory, Água Viva pursues life by mincing the lingering presence of the figure of the writer:

“I know that my phrases are crude, I write them with too much love, and that love makes up for their faults, but too much love is bad for the work. This isn’t a book because this isn’t how anyone writes. Is what I write a single climax? My days are a single climax: I live on the edge … This is life seen by life. I may not have meaning but it is the same lack of meaning that the pulsing vein has … What you will know of me is the shadow of the arrow that has hit its target.”

Repetitive, helplessly obsessive, and analytic, Lispector said of Água Viva, “That book, I spent three years without daring to publish it, thinking it would be awful. Because it didn’t have a story, it didn’t have a plot.” Earlier she told her close friend Olga Borelli that “I am not going to be autobiographical. I want to be ‘bio’ … I must find another way of writing. Very close to the truth (which?), but not personal.” The initial result was a longer manuscript called Loud Object which included trivial comment on Clarice’s everyday life. Olga become Clarice’s first editor (no one had touched her literary output before, only her journalism), excising the random material and shaping a stark, stricken narrative. As Moser notes, Água Viva “is attentive to each passing instant and electrified by the sad beauty of her inescapable destination: death, approaching with each tick of the clock.”

Repetitive, helplessly obsessive, and analytic, Lispector said of Água Viva, “That book, I spent three years without daring to publish it, thinking it would be awful. Because it didn’t have a story, it didn’t have a plot.” Earlier she told her close friend Olga Borelli that “I am not going to be autobiographical. I want to be ‘bio’ … I must find another way of writing. Very close to the truth (which?), but not personal.” The initial result was a longer manuscript called Loud Object which included trivial comment on Clarice’s everyday life. Olga become Clarice’s first editor (no one had touched her literary output before, only her journalism), excising the random material and shaping a stark, stricken narrative. As Moser notes, Água Viva “is attentive to each passing instant and electrified by the sad beauty of her inescapable destination: death, approaching with each tick of the clock.”

A few excerpts:

“I don’t want to have the terrible limitation of those who live merely from what can make sense. Not I: I want an invented truth.”

“I don’t know what I’m writing about: I am obscure to myself. I only had initially a lunar and lucid vision, and so I plucked for myself the instant before it died and perpetually dies. This is not a message of ideas that I am transmitted to you but an instinctive ecstasy of whatever is hidden in nature and that I foretell. And this is a feast of words. I write in signs that are more a gesture than voice. All this is what I got used to painting, delving into the intimate nature of things. But now the time to stop painting has come in order to remake myself, I remake myself in these lines. I have a voice. As I throw myself into the line of my drawing, this is an exercise in life without planning. The world has no visible order and all I have is the order of my breath. I let myself happen.”

“I want the profound organic disorder that nevertheless hints at an underlying order. The great potency of potentiality. These babbled phrases of mine are made the very moment they’re being written and are so new and green they crackle. They are the now. I want the experience of a lack of construction. Though this text of mine is crossed from end to end by a fragile connecting thread – which? That of a plunge into the matter of the world? Of passion? A lustful thread, breath that heats the passing of syllables. Life really just barely escapes me though the certainty comes to me that life is other and has a hidden style.”

“To live this life is more an indirect remembering than a direct living. It resembles a gentle convalescence from something that nonetheless could have been absolutely terrible. Convalescence from a frigid pleasure. Only for the initiates life then becomes fragilely truthful.”

“Why don’t I tackle a theme I could easily flush out? But no: I slink along the wall, I pilfer the flushed-out melody, I walk in the shadow, in that place where so many things go on.”

Água Viva is a sort of inverted version of The Cardboard House — and both “novels” make a similar appeal for “initiates.” The reader must be an accomplice, willing to forego the easily flushed-out theme. At first it seems there is more of the world to see in Adán, more of the human to feel in Lispector. But the final effects are remarkably similar. “The true thought seems to have no author,” writes Lispector. In pursuit of the very moment of ink to paper, whether the material at hand is memory or the very hand that holds the pen, Adán and Lispector created essential texts made of new instants in which we may see what is coming.

Água Viva is a sort of inverted version of The Cardboard House — and both “novels” make a similar appeal for “initiates.” The reader must be an accomplice, willing to forego the easily flushed-out theme. At first it seems there is more of the world to see in Adán, more of the human to feel in Lispector. But the final effects are remarkably similar. “The true thought seems to have no author,” writes Lispector. In pursuit of the very moment of ink to paper, whether the material at hand is memory or the very hand that holds the pen, Adán and Lispector created essential texts made of new instants in which we may see what is coming.

[Published by New Directions — The Cardboard House, translated by Katherine Silver. Published September 25, 2012, 120 pages, $15.95 paperback. Água Viva, newly translated by Stefan Tobler. Published June 13, 2012, 88 pages, $$14.95 paperback]

Note: New Directions has also reissued two other Lispector novels, Near To The Wild heart and The Passion According to G.H.

To listen to Allen Ginsberg read “To An Old Poet in Peru,” his poem for Martín Adán, click here.

Moser’s Bio

Just want to tell people that Ben Moser’s biography of Clarice Lispector is an inspiring and unique tale. Every serious writer should consider reading it, novelists and poets. She made her own way.

Her Novels Must Come First

Interesting that you decided to write about the most fragmented of the three Lispector reissues from New Directions. I’d recommend that anyone who really wants to get to know CL’s work should start with the more solid novels of hers. What gets me is that in her fifties she needed to write Agua Viva, after producing the novels that made her reputation. Something was definitely eating at her. Maybe it was the Spinoza?