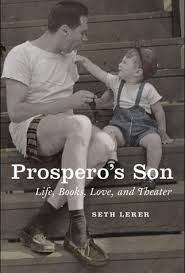

Seth Lerer’s parents met after being cast for a Brooklyn College production of Blithe Spirit in 1948. He was born in Brooklyn in 1955 and the family lived there until the mid-1960s when his father, Larry Lerer, then a junior high school history teacher seeking advancement, was admitted to Harvard’s Graduate School of Education at age 39. “Whenever we moved into a new town,” Lerer writes, “they would seek out the theatricals, much as someone else’s parents might seek out the church or the good schools.” The son was a troupe member: “I was put onstage almost as soon as I could talk.”

The theater of the family is the main act of Lerer’s memoir, Prospero’s Son. Although his family’s drama proved that “the genius of a great performance is to get you to imagine yourself in it,” his voice here maintains a modesty of expression. He makes few claims for himself. Handling the family’s behaviors as material, he can now imagine himself exiting stage right, finally able to sit in the audience with the rest of us and consider aspects of his life at a sedate remove. There is a winsome modesty in his spurning of knowingness; he does not confuse what he remembers with what he understands.

The theater of the family is the main act of Lerer’s memoir, Prospero’s Son. Although his family’s drama proved that “the genius of a great performance is to get you to imagine yourself in it,” his voice here maintains a modesty of expression. He makes few claims for himself. Handling the family’s behaviors as material, he can now imagine himself exiting stage right, finally able to sit in the audience with the rest of us and consider aspects of his life at a sedate remove. There is a winsome modesty in his spurning of knowingness; he does not confuse what he remembers with what he understands.

Lerer is the dean of arts and humanities at UC-San Diego. A lifelong academic, he is known for analyses of the English language and children’s literature. For this book, Lerer revised several previously published essays and stitched them together with a running narrative about the death of his father. I don’t give too much away by revealing that Lerer’s father ultimately divorced his mother to live openly as a gay man in San Francisco, since this fact is introduced early in the book:

“And then there was the night when I was eight when Dad failed to come home. Just months before, he had bought a new, silver Firebird convertible.” His mother told him in the morning that his father had attended a meeting and then been involved in a car crash but was unhurt. Fifteen years later, after the divorce, his mother recants, “The accident. Please. There was no meeting. It had been a tryst. You know what he is. I knew it when we married. I brought him home to meet my mother after we were in the Brooklyn College production of Blithe Spirit together. She said to me, ‘Who is this man who is an actor?’ And at the wedding, Aunt Gussie came up to me and said, ‘You know he’s a fagelah.’ Well, what did I care? I wanted to get out of that house, and he married me.”

“And then there was the night when I was eight when Dad failed to come home. Just months before, he had bought a new, silver Firebird convertible.” His mother told him in the morning that his father had attended a meeting and then been involved in a car crash but was unhurt. Fifteen years later, after the divorce, his mother recants, “The accident. Please. There was no meeting. It had been a tryst. You know what he is. I knew it when we married. I brought him home to meet my mother after we were in the Brooklyn College production of Blithe Spirit together. She said to me, ‘Who is this man who is an actor?’ And at the wedding, Aunt Gussie came up to me and said, ‘You know he’s a fagelah.’ Well, what did I care? I wanted to get out of that house, and he married me.”

The lapse of time between renditions extends to Lerer’s understated sense of pause and loss — the story may be told, at least in part, but not possessed. The son must solicit the memories of others to validate his own impressions of the father. One of Larry Lerer’s friends tells him, “The most important thing you need to understand about your father was that he was terrified of being alone. It wasn’t so much that he needed company but that he needed an audience.”

Recalling his family, Lerer observes “it was always a costumed life.” Its actual nature was meant to escape notice. As the essays proceed, Lerer lingers in the aftermath of his father’s death, taking inventory of possessions in the father’s San Francisco apartment. The absences, past and present, are palpable in the narrative, but Lerer treats them with a constrained melancholy.

There is more to Prospero’s Son than the family ordeal, including a fine and often comical essay on a post-college summer spent on an Icelandic farm. Lerer subtitles his book “Life, Books, Love, and Theater,” and this quartet functions as a set of compass points. But they don’t lead to gratifying destinations. The Tempest citings are too insistent and frilly. As for “life,” Lerer’s aloofness, so useful in modulating his tales of the family, prevents him from emerging as a dimensional presence, not that he ever intends to.

There is more to Prospero’s Son than the family ordeal, including a fine and often comical essay on a post-college summer spent on an Icelandic farm. Lerer subtitles his book “Life, Books, Love, and Theater,” and this quartet functions as a set of compass points. But they don’t lead to gratifying destinations. The Tempest citings are too insistent and frilly. As for “life,” Lerer’s aloofness, so useful in modulating his tales of the family, prevents him from emerging as a dimensional presence, not that he ever intends to.

Perhaps the “rough magic” in these essays is found in how Lerer pulls off a subtle vanishing act. Towards the end of the book in “Lithium Dreams,” we hear that he was given Thorazine and psychotherapy as a kid and that years later he collapsed into bed due to “the stress of coming up for tenure.” (The mother had been dosed with Milltown and Librium.) One wonders what else has been tucked away beneath Lerer’s affability. His relaxed narrative hovers over and enshadows the antagonisms, hurts and confusions that make it necessary. Although Prospero’s Son hews to the industry’s house style of memoir, the decorous script he writes for himself performs a salvaging mistrust of the performative.

* * * * * *

If Seth Lerer establishes an identity based on an enforced separation from his sources, in The Book of My Lives Aleksandar Hemon draws his persona by way of the anxiety of displacement. But where Lerer projects a lightly medicated thoughtfulness and wholeness, Hemon speaks more directly from ragged emotions inseparable from memory: anger, shame, anguish, disgust. Disinterested in Lerer’s more conventional decorum of memoir, he says, “I am nothing if not an entanglement of unanswerable questions.”

First, some facts. Hemon was born in Sarajevo in 1964. In his mid-20’s, he worked as a magazine culture editor and wrote some short fiction. Then, in the spring of 1991, the first reports of atrocities in Croatia began to circulate. In December, 1991, the United States Information Agency invited him to visit the U.S. to which he traveled in January, 1992. In May, the siege of Sarajevo began, cutting off the city’s lifelines. But Hemon’s family caught one of the last trains out of the city, and in December, 1993 they emigrated to Canada. Hemon settled in Chicago. In 1997, he returned to visit Sarajevo.

First, some facts. Hemon was born in Sarajevo in 1964. In his mid-20’s, he worked as a magazine culture editor and wrote some short fiction. Then, in the spring of 1991, the first reports of atrocities in Croatia began to circulate. In December, 1991, the United States Information Agency invited him to visit the U.S. to which he traveled in January, 1992. In May, the siege of Sarajevo began, cutting off the city’s lifelines. But Hemon’s family caught one of the last trains out of the city, and in December, 1993 they emigrated to Canada. Hemon settled in Chicago. In 1997, he returned to visit Sarajevo.

The shock of war and the stench of genocide pervade his attitude, not only regarding humanity but also about language itself and how it should be employed. In “The Lives of a Flaneur,” Hemon writes, “Nowadays in Sarajevo, death is all too easy to imagine and is continuously, undeniably present, but back then the city – a beautiful, immortal thing, an indestructible republic of urban spirit – was fully alive both inside and outside me. Its indelible sensory dimension, its concreteness, seemed to defy the abstractions of war. I have learned since then that war is the most concrete thing there can be, a fantastic reality that levels both interiority and exteriority into the flatness of a crushed soul.”

In the title essay, he recalls an admired literature professor who fell under the influence of Karadžić. Remembering, he is “racked with guilt” and speaks acidly about the “humanistic” literary perspective and feckless avant garde antics that blocked his view of the coming genocide. Hemon writes, “Now it seems clear to me that his evil had far more influence on me than his literary vision. I excised and exterminated that precious, youthful part of me that had believed you could retreat from history and hide form evil in the comfort of art. Because of Professor Koljević, perhaps, my writing is infused with testy impatience for bourgeois babbling, regrettably tainted with helpless rage I cannot be rid of.” Rage percolates through the shame of having abandoned Sarajevo: “If you were the author of a column entitled ‘Sarajevo Republika’ then it was perhaps hour duty to go back and defend your city and its spirit from annihilation.”

In the title essay, he recalls an admired literature professor who fell under the influence of Karadžić. Remembering, he is “racked with guilt” and speaks acidly about the “humanistic” literary perspective and feckless avant garde antics that blocked his view of the coming genocide. Hemon writes, “Now it seems clear to me that his evil had far more influence on me than his literary vision. I excised and exterminated that precious, youthful part of me that had believed you could retreat from history and hide form evil in the comfort of art. Because of Professor Koljević, perhaps, my writing is infused with testy impatience for bourgeois babbling, regrettably tainted with helpless rage I cannot be rid of.” Rage percolates through the shame of having abandoned Sarajevo: “If you were the author of a column entitled ‘Sarajevo Republika’ then it was perhaps hour duty to go back and defend your city and its spirit from annihilation.”

If you share my admiration for his prose fiction, Hemon’s The Book of My Lives will add a dimension to your understanding of the shaping of a writer’s sensibility. In “The Lives of Grand Masters,” he writes about playing chess with new acquaintances in Chicago, including an Assyrian born in Belgrade named Peter who became irritated by and shouted at some Loyola students babbling nearby: “I’d been annoyed by the incessant vacuousness of their exchange … Peter’s outburst, shocking thought it may have been, made perfect sense to me – not only did he deplore the waste of words, he detested the moral lassitude with which they were wasted. To him, in whose throat the bone of displacement was forever stuck, it was wrong to talk about nothing when there was a perpetual shortage of words for all the horrible things that happened in the world.”

Such is Hemon’s tone – impatient, sometimes intemperate, unappeasable, smoldering. The Book of My Lives collects and revises previously published essays on his youth and early adult years in Sarajevo, scrapes with state authority, his family and friends, the insidious approach and effects of war, and life in Chicago. The final stunning essay, “The Aquarium,” published as were five others here in The New Yorker, describes the days before the death of his infant daughter Isabel. Once again, as grief mounts to its highest level, language can barely keep up: “The world sailing calmly on depended on the language of functional platitudes and clichés that had no logical or conceptual connection to our catastrophe.”

Such is Hemon’s tone – impatient, sometimes intemperate, unappeasable, smoldering. The Book of My Lives collects and revises previously published essays on his youth and early adult years in Sarajevo, scrapes with state authority, his family and friends, the insidious approach and effects of war, and life in Chicago. The final stunning essay, “The Aquarium,” published as were five others here in The New Yorker, describes the days before the death of his infant daughter Isabel. Once again, as grief mounts to its highest level, language can barely keep up: “The world sailing calmly on depended on the language of functional platitudes and clichés that had no logical or conceptual connection to our catastrophe.”

Hemon mentions in an earlier essay that there is no word for “privacy” in the Bosnian language, “your fellow Sarajevans knew you as well as you knew them.” Perhaps the greatest respect Hemon pays is to regard his reader as a worthy intimate, even as such communal intimacy will be missed forever. The normalcy of life lost to history returns as a shared, evanescent moment of stricken acknowledgement.

[Prospero’s Son: Life, Books, Love and Theater, by Seth Lerer, published by the University of Chicago Press on April 5, 2013, 168 pages, $20.00 hardcover. The Book of My Lives, by Aleksandar Hemon, published by Farrar Straus & Giroux on March 19, 2013, 224 pages, $25.00 hardcover]

On Hemon

Many thanks for another excellent review. I reckon Hemon is a fatalist, and in his appeal to the reader, he is really asking that we don’t go as far as he had to go. This sort of intimacy must seem strange to the comfortable reader who has never dodged the bullet or heard the awful whistling. Or never seen the aftermath of that. Hemon could even be pursuing the “communal intimacy” himself, as a way to connect up the dots that keep the community of writers distanced from one another. It might magically succeed in connecting the reader to the readerly to the thing actually read. I’ve been similarly exercised when reading Stegner, Cormac McCarthy or Jim Harrison. If a novel is just a springboard, why does every act of reading have to just vanish in the air?