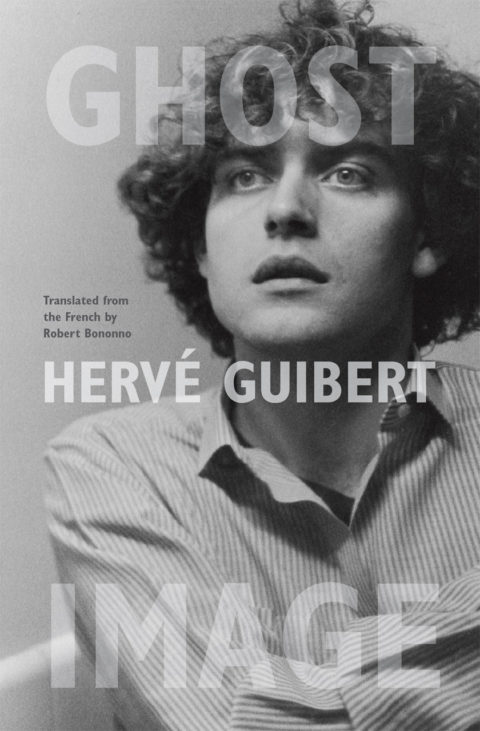

For his eighteenth birthday in 1973, Hervé Guibert received a Rollei 35 camera from his father. Eight years later in 1981, Guibert published L’image fantôme or Ghost Image, a collection of sixty-three short essays on photography that begins with a botched attempt to take a photograph of his mother shortly after receiving the gift. “The first thing I did,” begins the title essay, “was to remove my father from the room where the picture was to be taken, to chase him away so that her image would no longer pass through the one he had created of her … so that there was nothing left but our own complicity.”

Roland Barthes had published Camera Lucida the preceding year; the second part of that text was triggered by a photograph of his mother. During those years, Guibert was writing on photography and culture for Le Monde –and in Ghost Image he drew on, responded to, and departed from Barthes’ work. Guibert designed his story as “a negative of photography. It speaks of photography in negative terms, it speaks only of ghost images, images that have not yet issued, or rather, of latent images, images that are so intimate that they become invisible.”

Roland Barthes had published Camera Lucida the preceding year; the second part of that text was triggered by a photograph of his mother. During those years, Guibert was writing on photography and culture for Le Monde –and in Ghost Image he drew on, responded to, and departed from Barthes’ work. Guibert designed his story as “a negative of photography. It speaks of photography in negative terms, it speaks only of ghost images, images that have not yet issued, or rather, of latent images, images that are so intimate that they become invisible.”

The photograph of his mother was intended to capture her fleeting beauty on his own terms. After the session, he discovered that the film had not been properly loaded. “So this text will not have any illustrations except for a piece of blank film,” he continues. “For the text would not have existed if the picture had been taken.”

Ghost Image regards the photographic image as a body that will not yield the satisfactions of meaning despite the traces of actuality that seem to reside there. In his essay “Uses of Photography,” John Berger spelled out the enigma (quoting Susan Sontag at the end):

“Unlike memory, photographs do not in themselves preserve meaning. They offer appearances – with all the credibility and gravity we normally lend to appearances – prised away from their meaning. Meaning is the result of understanding functions. ‘And functioning takes place in time, and must be explained in time. Only that which narrates can make us understand.’ ”

Guibert’s essays, some quite brief, consider the silence of family snapshots, the eroticism of portraits, scenes and objects he might have shot, the urge to collect photos, the obsessions of scrutiny, pornography, travel photos, x-rays, Polaroids, self-portraits, retouched photos, identity card images, and the schism between the world and its representation.

Below, the entirety of “Photo Souvenir (East Berlin)”:

“N. gave me his photograph and, of course, I didn’t recognize him. I see only a better looking and more relaxed young man. But I can discover nothing of his original charm – his gentle smile, the indecisive wrinkle of his laugh. His address is written on the back on the photograph. I examine this face in vain, I can’t bring it any closer to the face I knew, I can’t reconstruct it. Yet I know that that face, the real one, is going to disappear completely from my memory, driven out by the tangible proof of the image. But soon, the image will mean nothing to me, and my own choice will be to throw it away or to hold on to it – the fragile souvenir of a hypocritical affection …”

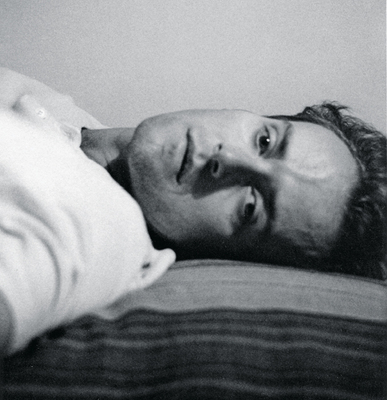

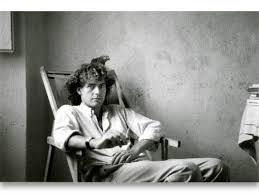

Hervé Guibert died in 1991 after suffering from AIDS for several years. Sade, Rimbaud, Genet, Artaud, and Bataille were his literary forebears; Michel Foucault was one of his closest friends. In 1990, with the publication of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, Guibert was one of the most outspoken and articulate public intellectuals speaking about the disease, reaching a mass audience through television appearances. Edmund White has noted that Guibert “must have realized that AIDS was not just a medical curiosity or a product of American hysteria but rather his destiny and his subject, one that would bring together his hatred of his own body, his taste for the grotesque and his infatuation with death … a pressure of fate brought to bear daily, hourly, on his previously aleatory existence.”

Hervé Guibert died in 1991 after suffering from AIDS for several years. Sade, Rimbaud, Genet, Artaud, and Bataille were his literary forebears; Michel Foucault was one of his closest friends. In 1990, with the publication of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, Guibert was one of the most outspoken and articulate public intellectuals speaking about the disease, reaching a mass audience through television appearances. Edmund White has noted that Guibert “must have realized that AIDS was not just a medical curiosity or a product of American hysteria but rather his destiny and his subject, one that would bring together his hatred of his own body, his taste for the grotesque and his infatuation with death … a pressure of fate brought to bear daily, hourly, on his previously aleatory existence.”

That existence, with all of its ferocity, is documented candidly in The Mausoleum of Lovers: Journals 1976-1991 (Nightboat Books). Both in the journals and his books, Guibert startles the reader through concision and finesse. The salaciousness is subject matter – but one courses through it via an unceasing, focused, committed curiosity. Also, his autofictions continuously imply a question: What does a successful piece of writing look and sound like? In Guibert, one finds a genius for narratives that create gathering force from the fragmentary – and a weary suspicion of the traditional novel’s form.

Ghost Image is essential Guibert – an artist’s penetrating look at his own profession and obsessions. It is animated and validated by prickly sensations and thrusts of thought that occur during composition – an accomplished photographer’s narrative that exists thanks to the virtuous failures of photos.

Ghost Image is essential Guibert – an artist’s penetrating look at his own profession and obsessions. It is animated and validated by prickly sensations and thrusts of thought that occur during composition – an accomplished photographer’s narrative that exists thanks to the virtuous failures of photos.

Like the body itself, the photos teach failure and catastrophe, yet they emit an energy that empowers the writer to articulate his own futility. Wayne Koestenbaum has remarked that Guibert is forever curious “about the worst things that can befall a body.” “The camera,” Guibert writes, “with its diaphragm, its shutter speeds, its carcasslike case is really a small, autonomous being. But it is a mutilated being that we have to carry around with us like an infant. It is heavy, noticeable, and we love it the same way we do an inform child who will never walk alone, but whose infirmity enables him to see the world with an acuity touched with madness.”

In 1986, Guibert published Mes parents, his eighth book of autofiction. The speaker recollects the moment his parents discover and disparage his homosexuality. At one point, he develops an infection on his foreskin; the father not only repeatedly applies ointment to the festering hurt, but also shows his own penis to the son. Then, some years later after having left home, the son returns on vacation, banishes his father from the parents’ bedroom, and photographs his mother in her lingerie. Once again, the pictures don’t properly develop and resulting images have a phantom aspect. The narrator says, they indicate something “other than imagery – towards narrative.”

In 1986, Guibert published Mes parents, his eighth book of autofiction. The speaker recollects the moment his parents discover and disparage his homosexuality. At one point, he develops an infection on his foreskin; the father not only repeatedly applies ointment to the festering hurt, but also shows his own penis to the son. Then, some years later after having left home, the son returns on vacation, banishes his father from the parents’ bedroom, and photographs his mother in her lingerie. Once again, the pictures don’t properly develop and resulting images have a phantom aspect. The narrator says, they indicate something “other than imagery – towards narrative.”

[Published by the University of Chicago Press on March 24, 2014. 160 pages, $18.00 paperback]

(Ghost Image was published in 1982 by Les Éditions de Minuit. Robert Bonanno’s translation appeared in 1996 from Sun and Moon Classics and is now reissued by the University of Chicago Press.)