A Nomadic Wedding

The groom has forgotten his shoes.

His best man, Nurbolat, gleefully spanks him, and Serikjan, the groom, grins sheepishly, glancing around at us. But in a moment his wide eyes look vacant again – he is startled to find himself on the way to his own wedding.

As they address the problem of the missing shoes, Dimitri, Dan, and I are assigned to affix balloons and magnetic hearts to the hood of Kaju’s Land Rover. Kaju is a professional driver and a friend. He lingers next to me as I inflate a balloon.

“Kamesbai,” he says, patting my shoulder and looking off into the distance.

When I first met Kaju, he willfully misheard my name as “Kamesbai,” and now addresses me only as such. He often insists to his friends that I am Kazakh, principally evinced by my faux-Kazakh name, which he then has me pronounce on cue.

Kaju is working with Nurbolat these days. The two have been driving us around Bayan-Olgii for the past week. Bayan-Olgii is Mongolia’s western-most province, both majority ethnically Kazakh and majority Muslim. Dimitri is in Mongolia on a research fellowship to record nomadic herders’ folksongs, and Nurbolat and Kaju are leading him around from musician to musician, constellating the countryside with Kazakh song. Dan and I, who are here respectively on an English-teaching fellowship and a study abroad semester, are along for the ride.

A few weeks ago, Nurbolat regretfully informed Dmitri, Dan, and I that we would have to change the dates of the trip unless we decided to attend a wedding with him. He told of drinking, feasts, all-night parties. We could not but accept.

Our two-car convoy is parked just below the crest of one of the steppe’s rolling hills. On the other side, it flattens out into a wide plain where the bride’s family lives. Serikjan switches shoes with his brother. Now his brother is wearing sandals, and Serikjan is wearing dress shoes. Nurbolat takes him aside to fix his tie.

Back in the cars, we crest the hill and descend towards the bride’s family’s home, which consists of two kiz uy — circular felt tents. Both the bride’s and the groom’s families are nomadic; the couple met in the province capital.

I initially wanted to study abroad in Mongolia to learn about nomadism whereby, I thought, I would learn about myself. My family has never lived anywhere for longer than five years, my father’s job moving us from New Jersey to Arizona to New Jersey to Wisconsin and then to London, England.

But I did not learn about myself in this way. Changing your home is not the same as moving your home. The former uproots you from the communities and landscapes that you know and understand. But the latter does not. Most herders return to the same places each year, moving between two and four times a year to seasonal pastures. The bride and groom have grown up in the same places and neighboring the same families. In fact, nomadic peoples have continuously populated the land now constituting Mongolia for several millennia, and many place names — of mountains, rivers, forests — have remained the same since at least the 1200s.

At the bride’s family’s camp, we are ushered into a very large kiz uy, in which there is an enormous spread of fruits, candies, chocolates, fried bread, homemade butter and more. A guest who has arrived before us half offers, half commands us to take shots of vodka with him. As foreigners, we are halfway between notable guests and drinking playthings. As the tent fills up, every new male guest that sits down within drinking distance of us makes us do the same.

At first the drink burns, but the vodka is good and my stomach is empty. By 11, I am solidly drunk. Dimitri whispers to me that he has been taking half shots; I am annoyed that he didn’t tell me this was allowed. The room appears watery as if all solid matter is only a husk filled with gelatin.

Dimitri snaps some pictures, but I know it’s too dark in here for my old film camera to capture anything.

I notice the bride, Guldauren, is here. She is not yet dressed in her gown and sits against the wall next to her bridesmaid. She stares absently at the floor, looks worried, a bit sad. Serikjan is sitting next to her, his brow furrowed, trying to occupy the same mental space as her, but Nurbolat keeps making him laugh at his jokes.

The room quiets down. A man of the bride’s family stands and begins speaking in Kazakh. Guldauren looks more and more despondent, her shoulders hunched, her head hung low, her face in a deep frown.

The mood turns somber. I sit as politely as possible, swaying only slightly, eyes on my shoes. Suddenly the speaker’s voice cracks, and I look up to see that he is crying. Guldauren has tears rolling down her cheeks, too. Other family members are wiping their eyes.

I suddenly realize, with sharp clarity, that this is the family’s final goodbye to their daughter, their niece, their granddaughter. The first speaker finishes, and the second begins. Guldauren is shuddering with tears, with the pain of a child being torn from home. The woman, her mother, speaks perhaps about what it meant to have her as a daughter, about her childhood, watching her grow up, the pain she feels at letting her go. Guldauren has lived in the same kiz uy for 21 years, has slept in the same room as her parents and her siblings almost every day, and is now leaving forever.

Now she is sobbing. Her mother, too. I feel the hot choke of tears lingering at the back of my throat. I think about the day I left my home to go to college, when my mom and I sat crying on the steps of our apartment building before the cab took me away. Not nearly so momentous as getting married, but perhaps the same stage in life.

Changing your home is not the same as moving your home, but neither is the same as leaving it.

The mood in the room lightens when the groom’s family comes in with velvety sacks the size of sheep, and gives them to members of the bride’s family. Serikjan’s father is a famous eagle hunter, once featured in a BBC documentary, and the sacks contain substantial gifts as a kind of dowry. Guldauren cries softly into her bridesmaid’s shoulder as the dowry is put away.

Soon the women of the family start to clear spaces in the spread, and huge platters of meat are carried in. Feasting ensues, and Kaju gleefully forces handfuls of liver meat and boiled sheep skin onto me, insisting I eat them despite the plethora of delicious thighbones being passed around. The roasted, fatty meat sobers me a little, but then more shots follow. My face feels very hot. Guldauren, who has not eaten, leaves to put on her gown.

We are outside again, the light breeze a cool refreshment. It is only about one or two in the afternoon. Images stutter in my memory — Kaju ordering me to take his photo with a friend, stepping over a short wall to pee behind it, Nurbolat disparaging Russian-made cars, the entire family posing for a photo, Guldauren still softly sobbing.

They gather around her and Serikjan: the aunts, uncles, cousins, siblings, in-laws, nieces, nephews. The arc of bodies seems to cradle her one last time. It is almost unbearable to finally cross that chasm between the family and the car. And then, she is ushered across into Kaju’s Land Rover with Serikjan, Nurbolat, the bridesmaid, and they pull away.

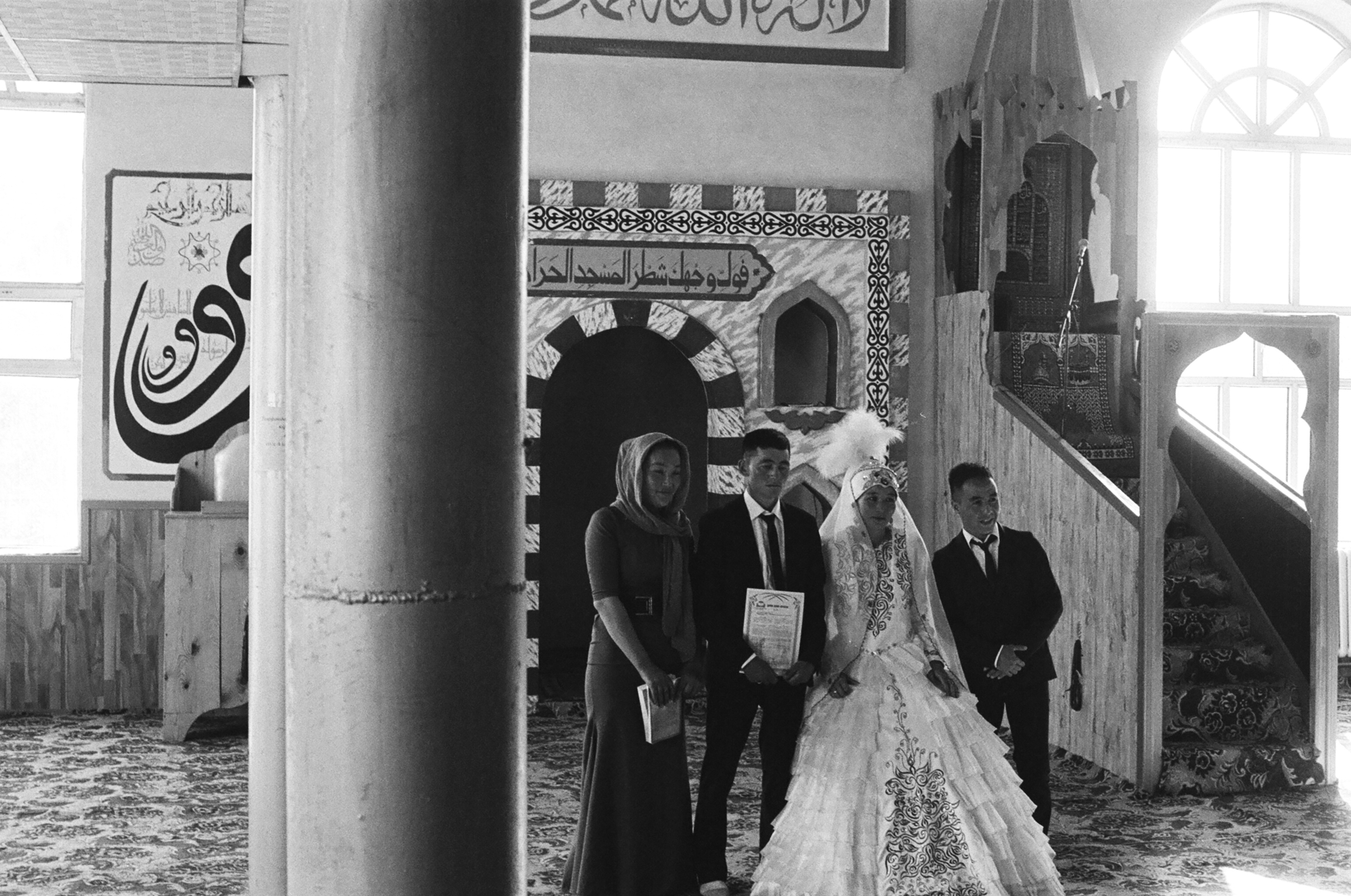

Then we are in Serikjan’s brother’s car, racing over the undulant hills towards Olgii, buoyed about in the sea of land. In the mosque, we rejoin Kaju, Nurbolat, and the bride and groom. The ceremony is brief, attended only by immediate family and, for some reason, Dimitri, Dan and I. We take off our shoes at the door and sit cross-legged with our backs to the wall. I stare at my socks as the imam leads them through their vows.

At the dinner that evening, there is more food, more drink, hundreds of people. Guldauren still looks despondent but has stopped crying. The party transitions to a music hall. A singer comes on stage with a dombra, a two-stringed Kazakh lute, and begins to play. The room is washed in sound, in the sonorous rasp of the singer’s voice, the lilting, mournful twangs of the dombra. Guldauren’s frown lifts a little. The sound fills the room until it seeps out into the soft night, where the wind blows down the dusty streets and into the grassy steppe, which furrows into the Altai Mountains and flattens again into Kazakhstan, then further to the Caspian, Russia, Europe, the Atlantic, America.